Although some authors credit Elijah Craig as the “Father of Bourbon,” others have challenged that designation declaring that while Craig was an early Kentucky distiller it is unlikely that he was making bourbon whiskey. For me, Craig’s place in history is not about whiskey but about his championing of religious freedom.

Although some authors credit Elijah Craig as the “Father of Bourbon,” others have challenged that designation declaring that while Craig was an early Kentucky distiller it is unlikely that he was making bourbon whiskey. For me, Craig’s place in history is not about whiskey but about his championing of religious freedom.

Elijah was born about 1738 in Orange County, Virginia, the fifth child of Polly Hawkins and Toliver Craig. From his boyhood he displayed unusual intellectual gifts, with a strong streak of religiosity. Virginia was state where all residents were required by law to tithe to the Anglican Church and attend Anglican worship at least once a month. The official faith was deemed by elite Virginians as essential element of the commonwealth’s social structure. Other theological ideas were in the air, however, with Baptists considered by many to be particularly dangerous.

Early Baptists faced opposition. By law they were required to obtain licenses in order to preach, documents that often specified the place of worship and, in effect, outlawed itinerant circuit riders and tent meetings. When ministers balked at those restrictions, they often were jailed. Baptists also were subject to verbal and physical abuse. David Thomas, a Baptist missionary to Virginia, was attacked while conducting a home service in Fauquier County and brutally beaten. Later he would survive an assassination attempt.

Early Baptists faced opposition. By law they were required to obtain licenses in order to preach, documents that often specified the place of worship and, in effect, outlawed itinerant circuit riders and tent meetings. When ministers balked at those restrictions, they often were jailed. Baptists also were subject to verbal and physical abuse. David Thomas, a Baptist missionary to Virginia, was attacked while conducting a home service in Fauquier County and brutally beaten. Later he would survive an assassination attempt.

Nevertheless, Craig was drawn to Baptist beliefs by Thomas and in the mid-1860s began to hold meetings in his tobacco barn. In 1866, along with other family members, he was formally baptized. Full of fervor, he began to preach even though still a layman, resulting in his being jailed in Fredericksburg for several weeks for preaching without a license. Ordained in 1771 Craig became the pastor of a small Virginia church. Unwilling to submit to obtaining a license, he was jailed several more times.

A contemporary wrote of his oratory: “His preaching was of the most solemn style; his appearance as of a man who had just come from the dead; of a delicate habit, a thin visage, large eyes and mouth; the sweet melody of his voice, both in preaching and singing, bore all down before it.”

Following the American Revolution Craig was politically active as the Baptist representative to the Virginia legislature, said to have worked with Patrick Henry and James Madison to protect religious freedom in Virginia and at the federal level. The Church of England was “disestablished,” i.e., lost government financial support. Baptist ideals of “separation of church and state” took hold.

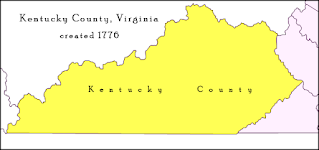

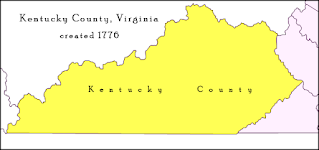

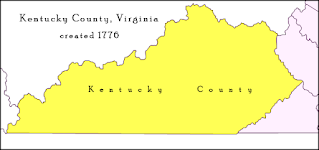

Throughout this period while preaching and pastoring, Craig was engaged in agricultural activities, likely including distilling some of his corn crop into the “white lightning” early Americans called whiskey. Craig pulled up stakes in Orange County and led his congregation west to the newly formed “Kentucky County” in western Virginia. There he purchased 1,000 acres of land where he planned and laid out a town, below, that came to be named “Georgetown,” honoring George Washington. Kentucky County would achieve statehood in 1788.

Throughout this period while preaching and pastoring, Craig was engaged in agricultural activities, likely including distilling some of his corn crop into the “white lightning” early Americans called whiskey. Craig pulled up stakes in Orange County and led his congregation west to the newly formed “Kentucky County” in western Virginia. There he purchased 1,000 acres of land where he planned and laid out a town, below, that came to be named “Georgetown,” honoring George Washington. Kentucky County would achieve statehood in 1788.

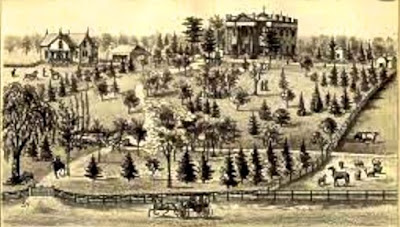

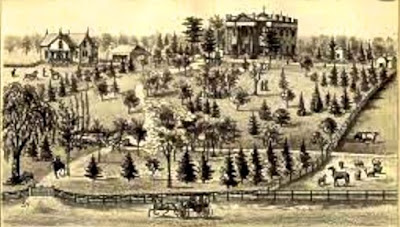

As he entered middle age, Craig’s ability and apparent limitless energy came into full flower. While continuing to serve as pastor to a Baptist congregation in 1787 he established the first classical school in Kentucky and later donated the land for what became Georgetown College, the first Baptist college west of the Alleghenies, shown left. Craig was an early industrialist, in Georgetown building the state’s first textile plant, first rope manufactory, first lumber mill, first paper mill, and a gristmill. Aware of the dangers posed by conflagrations and with a lot to lose, Craig also formed the town’s first fire department and became its chief.

As he entered middle age, Craig’s ability and apparent limitless energy came into full flower. While continuing to serve as pastor to a Baptist congregation in 1787 he established the first classical school in Kentucky and later donated the land for what became Georgetown College, the first Baptist college west of the Alleghenies, shown left. Craig was an early industrialist, in Georgetown building the state’s first textile plant, first rope manufactory, first lumber mill, first paper mill, and a gristmill. Aware of the dangers posed by conflagrations and with a lot to lose, Craig also formed the town’s first fire department and became its chief.

About 1789, Craig took his place in whiskey history by building a distillery, making use of the cold stream of pure water coming from Georgetown’s Royal Spring, giving rise to the idea that he “invented” bourbon. At the time, dozens of small farmer-distillers west of the Alleghenies were making whiskey from corn that some called “bourbon” to distinguish it from the rye whiskies coming from Pennsylvania and Maryland. True bourbon, however, must be aged in charred barrels that impart color and flavor.

About 1789, Craig took his place in whiskey history by building a distillery, making use of the cold stream of pure water coming from Georgetown’s Royal Spring, giving rise to the idea that he “invented” bourbon. At the time, dozens of small farmer-distillers west of the Alleghenies were making whiskey from corn that some called “bourbon” to distinguish it from the rye whiskies coming from Pennsylvania and Maryland. True bourbon, however, must be aged in charred barrels that impart color and flavor.

Several theories have been offered about how Craig created bourbon. One is that a barn fire charred the inside of some of the barrels he used for his whiskey. When aged in those charred oak barrels, the whiskey took on some of the color and flavor, giving it a more mellow, sweeter flavor. Another is that, as a frugal pastor, Craig wanted to be able to reuse barrels that had previously stored fish and salt. In that story, he intentionally charred the inside of the oak barrels to remove the fish flavor before aging his whiskey within. There is no proof for either theory.

Nonetheless the legend stands, repeated over and over. Whiskey guru Michael Veach has a plausible suggestion of how the Elijah Craig story got started: “He was an early Kentucky preacher and he was a distiller, and that is why in the 1870s when the distilling industry was fighting the temperance movement, they decided to proclaim him the father of bourbon. They thought, well, let’s make a Baptist preacher the father of bourbon, and let the temperance people deal with that.”

Craig eventually owned more than 4,000 acres and enough slaves to cultivate it, and operated a retail store in Frankfort, Kentucky. His whiskey does not seem to have had more than a local reputation and his other enterprises not always were successful. When he died in Georgetown in 1808, The Kentucky Gazette eulogized Craig as follows: “He possessed a mind extremely active and, as his whole property was expended in attempts to carry his plans to execution, he consequently died poor. If virtue consists in being useful to our fellow citizens, perhaps there were few more virtuous men than Mr. Craig.”

Today Heaven Hill Distilleries in Bardstown, Kentucky, is happy to perpetuate the bourbon legend. Elijah Craig bourbon whiskey is made in both 12-year-old “Small Batch” and 18-year-old “Single Barrel” bottlings. The latter is touted by the distillery as “The oldest Single Barrel Bourbon in the world at 18 years ….” said to be aged in hand selected oak barrels that lose nearly 2⁄3 of their contents in the evaporation, known as the “Angel’s share.” Needless to say the whiskey is pricey.

Notes: A considerable number of sources were consulted for this post. Most important for details on Craig’s stance on religious freedom was an article in Wikipedia. The drawing of Craig that opens this post is the only likeness of the preacher/distiller to be found. It may or may not bear any resemblance to the original. Finally, in my only visit to the Heaven Hill Distillery some years ago, the brand coming off the bottling and labeling line was “Elijah Craig.” No one offered me a sample.

Although some authors credit Elijah Craig as the “Father of Bourbon,” others have challenged that designation declaring that while Craig was an early Kentucky distiller it is unlikely that he was making bourbon whiskey. For me, Craig’s place in history is not about whiskey but about his championing of religious freedom.

Although some authors credit Elijah Craig as the “Father of Bourbon,” others have challenged that designation declaring that while Craig was an early Kentucky distiller it is unlikely that he was making bourbon whiskey. For me, Craig’s place in history is not about whiskey but about his championing of religious freedom.

Elijah was born about 1738 in Orange County, Virginia, the fifth child of Polly Hawkins and Toliver Craig. From his boyhood he displayed unusual intellectual gifts, with a strong streak of religiosity. Virginia was state where all residents were required by law to tithe to the Anglican Church and attend Anglican worship at least once a month. The official faith was deemed by elite Virginians as essential element of the commonwealth’s social structure. Other theological ideas were in the air, however, with Baptists considered by many to be particularly dangerous.

Early Baptists faced opposition. By law they were required to obtain licenses in order to preach, documents that often specified the place of worship and, in effect, outlawed itinerant circuit riders and tent meetings. When ministers balked at those restrictions, they often were jailed. Baptists also were subject to verbal and physical abuse. David Thomas, a Baptist missionary to Virginia, was attacked while conducting a home service in Fauquier County and brutally beaten. Later he would survive an assassination attempt.

Early Baptists faced opposition. By law they were required to obtain licenses in order to preach, documents that often specified the place of worship and, in effect, outlawed itinerant circuit riders and tent meetings. When ministers balked at those restrictions, they often were jailed. Baptists also were subject to verbal and physical abuse. David Thomas, a Baptist missionary to Virginia, was attacked while conducting a home service in Fauquier County and brutally beaten. Later he would survive an assassination attempt.

Nevertheless, Craig was drawn to Baptist beliefs by Thomas and in the mid-1860s began to hold meetings in his tobacco barn. In 1866, along with other family members, he was formally baptized. Full of fervor, he began to preach even though still a layman, resulting in his being jailed in Fredericksburg for several weeks for preaching without a license. Ordained in 1771 Craig became the pastor of a small Virginia church. Unwilling to submit to obtaining a license, he was jailed several more times.

A contemporary wrote of his oratory: "His preaching was of the most solemn style; his appearance as of a man who had just come from the dead; of a delicate habit, a thin visage, large eyes and mouth; the sweet melody of his voice, both in preaching and singing, bore all down before it."

Following the American Revolution Craig was politically active as the Baptist representative to the Virginia legislature, said to have worked with Patrick Henry and James Madison to protect religious freedom in Virginia and at the federal level. The Church of England was “disestablished,” i.e., lost government financial support. Baptist ideals of “separation of church and state” took hold.

Throughout this period while preaching and pastoring, Craig was engaged in agricultural activities, likely including distilling some of his corn crop into the “white lightning” early Americans called whiskey. Craig pulled up stakes in Orange County and led his congregation west to the newly formed “Kentucky County” in western Virginia. There he purchased 1,000 acres of land where he planned and laid out a town, below, that came to be named “Georgetown,” honoring George Washington. Kentucky County would achieve statehood in 1788.

Throughout this period while preaching and pastoring, Craig was engaged in agricultural activities, likely including distilling some of his corn crop into the “white lightning” early Americans called whiskey. Craig pulled up stakes in Orange County and led his congregation west to the newly formed “Kentucky County” in western Virginia. There he purchased 1,000 acres of land where he planned and laid out a town, below, that came to be named “Georgetown,” honoring George Washington. Kentucky County would achieve statehood in 1788.

As he entered middle age, Craig’s ability and apparent limitless energy came into full flower. While continuing to serve as pastor to a Baptist congregation in 1787 he established the first classical school in Kentucky and later donated the land for what became Georgetown College, the first Baptist college west of the Alleghenies, shown left. Craig was an early industrialist, in Georgetown building the state’s first textile plant, first rope manufactory, first lumber mill, first paper mill, and a gristmill. Aware of the dangers posed by conflagrations and with a lot to lose, Craig also formed the town’s first fire department and became its chief.

As he entered middle age, Craig’s ability and apparent limitless energy came into full flower. While continuing to serve as pastor to a Baptist congregation in 1787 he established the first classical school in Kentucky and later donated the land for what became Georgetown College, the first Baptist college west of the Alleghenies, shown left. Craig was an early industrialist, in Georgetown building the state’s first textile plant, first rope manufactory, first lumber mill, first paper mill, and a gristmill. Aware of the dangers posed by conflagrations and with a lot to lose, Craig also formed the town’s first fire department and became its chief.

About 1789, Craig took his place in whiskey history by building a distillery, making use of the cold stream of pure water coming from Georgetown’s Royal Spring, giving rise to the idea that he “invented” bourbon. At the time, dozens of small farmer-distillers west of the Alleghenies were making whiskey from corn that some called “bourbon” to distinguish it from the rye whiskies coming from Pennsylvania and Maryland. True bourbon, however, must be aged in charred barrels that impart color and flavor.

About 1789, Craig took his place in whiskey history by building a distillery, making use of the cold stream of pure water coming from Georgetown’s Royal Spring, giving rise to the idea that he “invented” bourbon. At the time, dozens of small farmer-distillers west of the Alleghenies were making whiskey from corn that some called “bourbon” to distinguish it from the rye whiskies coming from Pennsylvania and Maryland. True bourbon, however, must be aged in charred barrels that impart color and flavor.

Several theories have been offered about how Craig created bourbon. One is that a barn fire charred the inside of some of the barrels he used for his whiskey. When aged in those charred oak barrels, the whiskey took on some of the color and flavor, giving it a more mellow, sweeter flavor. Another is that, as a frugal pastor, Craig wanted to be able to reuse barrels that had previously stored fish and salt. In that story, he intentionally charred the inside of the oak barrels to remove the fish flavor before aging his whiskey within. There is no proof for either theory.

Nonetheless the legend stands, repeated over and over. Whiskey guru Michael Veach has a plausible suggestion of how the Elijah Craig story got started: “He was an early Kentucky preacher and he was a distiller, and that is why in the 1870s when the distilling industry was fighting the temperance movement, they decided to proclaim him the father of bourbon. They thought, well, let’s make a Baptist preacher the father of bourbon, and let the temperance people deal with that.”

Craig eventually owned more than 4,000 acres and enough slaves to cultivate it, and operated a retail store in Frankfort, Kentucky. His whiskey does not seem to have had more than a local reputation and his other enterprises not always were successful. When he died in Georgetown in 1808, The Kentucky Gazette eulogized Craig as follows: "He possessed a mind extremely active and, as his whole property was expended in attempts to carry his plans to execution, he consequently died poor. If virtue consists in being useful to our fellow citizens, perhaps there were few more virtuous men than Mr. Craig.”

Today Heaven Hill Distilleries in Bardstown, Kentucky, is happy to perpetuate the bourbon legend. Elijah Craig bourbon whiskey is made in both 12-year-old "Small Batch" and 18-year-old "Single Barrel" bottlings. The latter is touted by the distillery as "The oldest Single Barrel Bourbon in the world at 18 years ….” said to be aged in hand selected oak barrels that lose nearly 2⁄3 of their contents in the evaporation, known as the “Angel’s share.” Needless to say the whiskey is pricey.

Notes: A considerable number of sources were consulted for this post. Most important for details on Craig’s stance on religious freedom was an article in Wikipedia. The drawing of Craig that opens this post is the only likeness of the preacher/distiller to be found. It may or may not bear any resemblance to the original. Finally, in my only visit to the Heaven Hill Distillery some years ago, the brand coming off the bottling and labeling line was “Elijah Craig.” No one offered me a sample.