So, yeah. I’m still sick enough that I don’t have the brainpower to write. Also, my taste buds are still mighty screwed up, so tasting accurately just isn’t happening. And that totally sucks. But I’m getting better every day, so don’t feel too bad for me. Instead of giving you no content, I’ve decided to repost an educational article from way back in 2015. Guessing not many of you were around for this, so hopefully, it is good info or at least entertaining info.

A few days ago, I got an email from Tom asking about barrel proof.

Hi Arok…

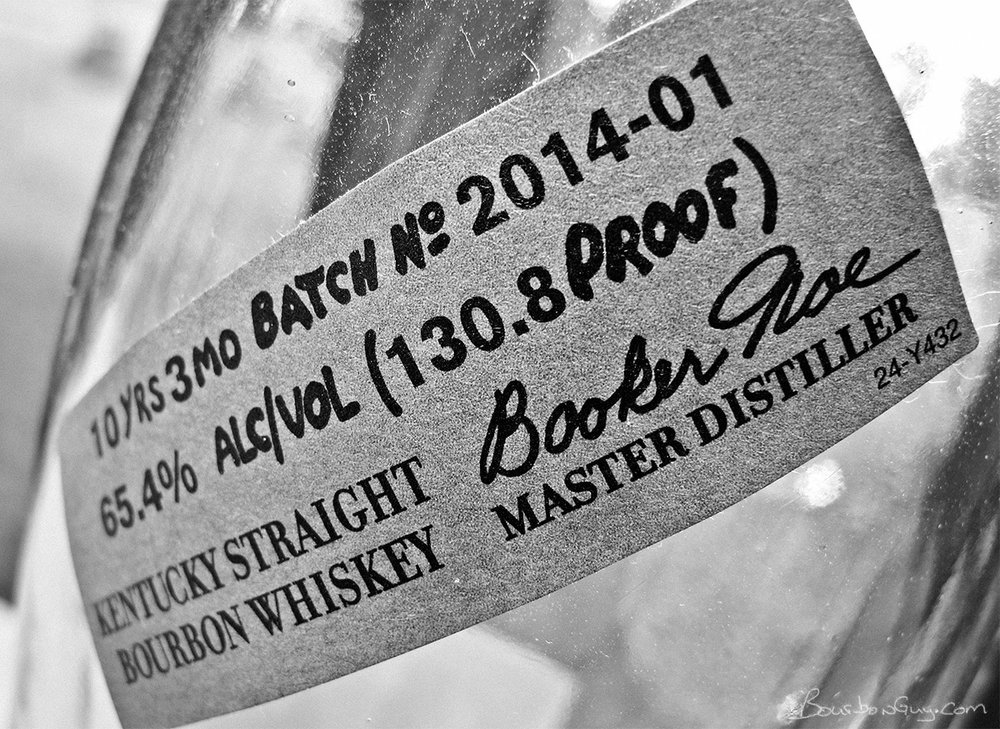

I need a little clarification. I just received a bottle of "Booker’s” in a nice box, as a gift. The label says single barrel 127 proof. It aroused my curiosity. Then I read that Garrison Brothers have a new release "Cowboy Bourbon" @ 134 proof (not for the faint of heart)....! I thought to be "Bourbon.” whiskey had comply with certain criteria one of which is that it couldn't be barreled at higher than 125 proof … what’s the story here?

Thanks for your help.

Tom

Tom asks a great question. To answer it, we need to dig a little into the science behind aging. While it is true that bourbon can’t be barreled at higher than 125 proof, that is only true for the liquid going into the barrel. What happens after that is up to nature.

Let’s take a look at what happens during aging. Three basic things are going on: extraction of flavor, chemical reactions, and then the interaction with the surrounding environment (which is where Tom's question comes in). So to look at each in turn:

Extraction of flavor: Alcohol is a solvent; like all solvents, it loves to dissolve things. In the case of bourbon, what is being dissolved are all the caramel and vanilla flavors that burning a piece of oak allows the alcohol access to. This happens pretty quickly in the grand scheme of things. It’s why you can get something that tastes like “bourbon” at six months or less in a small barrel. It doesn’t taste exactly like the large, mainstream bourbons, but it has a lot of the same characteristics. At this point, it is a wood extract, much like the vanilla extract you’d find in your kitchen cupboards. Only in this case, we have wood flavors dissolved in the alcohol, not vanilla bean flavors.

Chemical Reactions: This is a function of time. Certain things happen to that extract as time passes while it is in the presence of oxygen. Molecules break down and recombine into tasty combinations that give a well-matured whiskey a lot of the tasty flavors we associate with it. How does that oxygen get into the barrel? A properly constructed barrel is very good at keeping liquid inside but, luckily, isn’t so good at keeping air inside (or outside).

This brings us to the answer to Tom's question: interaction with the environment. In general terms, if you were to look at both the ethanol molecule and the water molecule, you would notice something. The ethanol molecule is much larger. As such, the water molecule can more easily pass through the grain of the oak being used in the barrel. This means that two things can happen:

In a hot environment, such as the upper floors of a rick house in Kentucky, water and ethanol evaporate. The water passes through the wood, but the alcohol stays behind. As such, the alcohol per volume of the liquid goes up as the volume of liquid goes down due to the water escaping. This is why a barrel-proof bourbon such as Bookers or Stag can be higher in proof than the liquid that originally went into the barrel.

Just the opposite happens in a cool, moist environment, such as the bottom floor of a rick house with a dirt floor. It’s cool enough that there isn’t as much evaporation happening, but the air going in and out of the barrel, being moist, is bringing water into the barrel. And so the total alcohol by volume goes down as the volume of water goes up. This is why the first Wild Turkey Master’s Keep, even at 17 years old, can be barrel-proof at well below the proof that it went into the barrel.

Of course, this is just a simplified version of the science behind aging. People with degrees in more than art probably can give all the charts and more specific reasons behind these processes, but this is how it was explained to me.

Do you have a bourbon question you'd like answered? Just shoot me an email or leave a comment below.

Did you enjoy this post? If so, maybe you’d like to buy me a cup of coffee in return. Go to ko-fi.com/bourbonguy to support. And thank you, BourbonGuy.com is solely supported via your generosity.

Of course, if you want to support BourbonGuy.com and get a little something back in return, you can always head over to BourbonGuyGifts.com and purchase some merch. I’ve made tasting journals, stickers, pins, posters, and more.