Fans of the movie version of Anne Rice’s “Interview with the Vampire” will recognize at right the New Orleans above-ground tomb of her blood-sucking hero, Lestat. When visiting Lafayette Cemetery #1, tourists often seek out the cast-iron crypt and wonder who actually is interred there. It is Otto Henry Karstendieck, a liquor dealer whose life, like Lestat’s, contained more than sufficient horror, death and deception to make his tale worth telling. Otto’s story, in contrast to Rice’s, is non-fiction.

Fans of the movie version of Anne Rice’s “Interview with the Vampire” will recognize at right the New Orleans above-ground tomb of her blood-sucking hero, Lestat. When visiting Lafayette Cemetery #1, tourists often seek out the cast-iron crypt and wonder who actually is interred there. It is Otto Henry Karstendieck, a liquor dealer whose life, like Lestat’s, contained more than sufficient horror, death and deception to make his tale worth telling. Otto’s story, in contrast to Rice’s, is non-fiction.

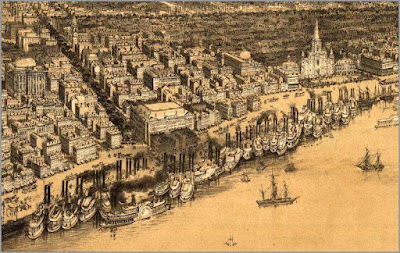

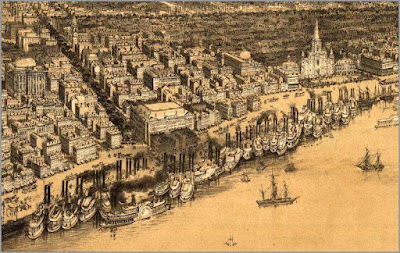

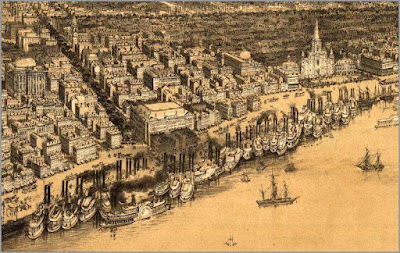

Otto was born on April 21, 1823, in Bremen, Germany, the son of Heinrich and Anna Metta Karstendiek. Of his early life and education the record is blank, as well as is the exact date of his coming to America, apparently around 1850. What propelled him to New Orleans similarly is obscure. The first public record I can find is 1856 when he was 33 years old and New Orleans was a booming city, shown below. In May of that year Otto married Delia Cecelia Salomon, whose claim to fame was being the sister of the first “Rex” of the Mardi Gras parade. Over the next eight years the couple would have five children, two daughters and three sons.

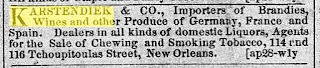

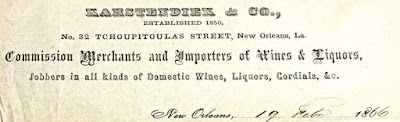

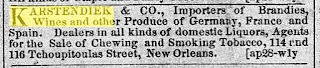

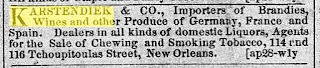

Meanwhile Otto was demonstrating his abilities as a liquor and wine dealer, claiming his liquor house origin as 1850. From his Tchoupoulas Street headquarters in uptown New Orleans close to the Mississippi River, as early as 1853 he was advertising in a wide area beyond Louisiana. A Galveston newspaper ad declared Karstendiek & Company an importer of European brandies and wines as well as “Dealers in all kinds of domestic liquors….” By the end of the decade Otto was doing business from two warehouses, each four stories high, a block long and filled with liquor.

Meanwhile Otto was demonstrating his abilities as a liquor and wine dealer, claiming his liquor house origin as 1850. From his Tchoupoulas Street headquarters in uptown New Orleans close to the Mississippi River, as early as 1853 he was advertising in a wide area beyond Louisiana. A Galveston newspaper ad declared Karstendiek & Company an importer of European brandies and wines as well as “Dealers in all kinds of domestic liquors….” By the end of the decade Otto was doing business from two warehouses, each four stories high, a block long and filled with liquor.

On Saturday, October 13, 1860, tragedy struck. About 8 p.m. a large fire of undetermined origin broke out in one Karstendiek warehouse. Soon the structure was engulfed in flames from the ground floor to the roof, imperiling the second warehouse. When the fire reached the top floor where considerable liquor was stored, a tremendous explosion occurred, destroying both warehouses and spreading the fire to adjoining structures.

On Saturday, October 13, 1860, tragedy struck. About 8 p.m. a large fire of undetermined origin broke out in one Karstendiek warehouse. Soon the structure was engulfed in flames from the ground floor to the roof, imperiling the second warehouse. When the fire reached the top floor where considerable liquor was stored, a tremendous explosion occurred, destroying both warehouses and spreading the fire to adjoining structures.

The New Orleans Picayune reported: “No battlefield, no steamboat explosion could exceed the horror of the scene. There under the enormous mass of smoking ruins, thirty or forty men lay buried.” Chief among them were members of New Orleans volunteer fire companies that had responded to the alarm and were pour water on the first warehouse. The paper listed names and units of men pulled dead, dying or injured in the explosion. Among those who barely escaped was the New Orleans chief of police. Rescue efforts were hampered by the intense heat of the fire. “Many, many more remained buried under the ruins,as we left the scene. Two had been heard to speak, but could not be reached and, horrible to relate, they stated that the fire was burning the timbers underneath, and gaining upon them,” the newspaper reported.

Otto does not seem to have been on the premises when the fire occurred. While he sustained the loss of his buildings and some stock, quantities of the whiskey he was storing reputedly were owned by second parties. Although I can find no information on the total death count or monetary loss the latter would be the equivalent today of millions.

It is likely that among the dead and injured were Karstendiek & Co. employeeswhose deaths Otto would have mourned as he attempted to collect on his insurance and rebuild his business at a new location on Tchoupoulas Street. He continued to advertise widely as: “Dealers in Old Bourbon, Rye. Monogahela. Tennessee white, Roblnson county, White Wheat, and common whiskey.”

The advent of the Civil War proved a boon to Otto. Although initially revenues in the city fell with Union occupation, a “welfare state” was created by federal authorities to alleviate “the deplorable state of destitution and hunger of the mechanics and working classes of the city.” It was paid for by a special tax on the wealthy and businesses. Revenues allowed the military government to employ 2,000 men daily to clean up the city. The levy also generated relief payments to 11,000 families, most of whom were Irish and German. Moreover, Union forces in New Orleans and vicinity grew to 17,800. The customer base for Otto’s liquor swelled.

The end of the Civil War brought a double setback. After the birth of their fifth child, the health of Otto’s wife Delia declined and after just nine years of marriage in November 1865 she died at the age of 29. Her husband was left with the sole care of five children, the oldest nine, the youngest a toddler. Five years later Otto remarried. His new spouse was Ella Lavernia Stoddard from Albany, New York. They would have one son.

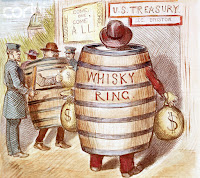

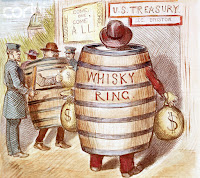

The second blow was the reduced revenues Otto was facing in New Orleans during Reconstruction. Gone were the subsidies for workers and the payroll of a large standing army. The customer base for Karstendiek & Company dwindled sharply. Otto decided to “go to the dark side.” He joined in what came to be known as “The Whiskey Ring,” a massive scheme to cheat the federal government of millions of dollars in liquor revenues. Hatched in 1871 by a top Grant Administration revenue official in St. Louis, the conspiracy had its tentacles in Chicago, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and stretched south to New Orleans.

There President Grant had appointed his wife’s brother-in -law, Col. James B. Case, as collector of customs for the port. Casey was quick to see the ease and financial possibilities of skimming off illicit cash from liquor taxes. He recruited a handful of New Orleans distillers and liquor dealers to assist him in the scheme. Among them was Otto Karstendiek.

In addition to selling whiskey and other alcoholic products at wholesale and retail,

Otto was a “rectifier,” that is, someone blending raw whiskeys on his premises in order to achieve a specific color, smoothness and taste. Because the blending added value to the product, rectifiers were required to keep detailed records and were taxed on the amount of product blended. By variety of mean, from corrupt federal “gaugers” who falsified production or the use of fraudulent revenue stamps, the U.S. Treasury was cheated out of millions.

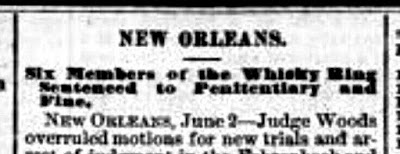

The Whiskey Ring came to abrupt halt on May 10, 1875, when U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin Bristow, working without the knowledge of President Grant, broke up the tightly connected and politically powerful cabal. He used secret agents from outside the Treasury Department to conduct a series of raids across the country on May 10, 1875. Among those arrested was Otto Karstendiek.

The Whiskey Ring came to abrupt halt on May 10, 1875, when U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin Bristow, working without the knowledge of President Grant, broke up the tightly connected and politically powerful cabal. He used secret agents from outside the Treasury Department to conduct a series of raids across the country on May 10, 1875. Among those arrested was Otto Karstendiek.

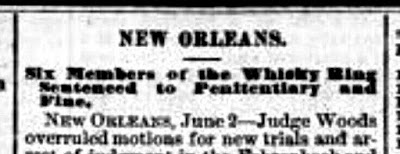

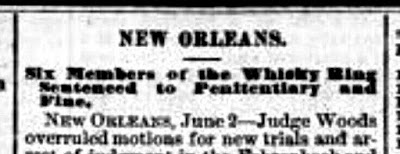

Otto and his co-conspirators did not come to trial until almost a full year after the raid. In the interim the German whiskey man had suffered another heartbreaking loss. Ella, his wife of just four years, died in September 1875, leaving him with a sixth motherless child. At his trial in the U.S. Circuit for the District of Louisiana in May 1875, Otto and five of his co-conspirators were found guilty and sentenced. James Casey was not among them. The prisoners were fined from $1,000 to $6,000 and sentenced to prison variably from six to sixteen months. Otto was assessed $1000 and maximum prison time.

All six were sent to the State Penitentiary at Moundsville, West Virginia, shown here, more than 1,000 miles from Otto’s New Orleans home. He must have been anguished at serving time so far from his children, now to be looked after by others. Although his liquor house was shut briefly as the result of his folly, Otto still had resources. While serving time at Moundsville, he hired a lawyer and thus was born a case before the U.S. Supreme Court at its 1876 October term, entitled “Ex Parte Karstendiek.”

All six were sent to the State Penitentiary at Moundsville, West Virginia, shown here, more than 1,000 miles from Otto’s New Orleans home. He must have been anguished at serving time so far from his children, now to be looked after by others. Although his liquor house was shut briefly as the result of his folly, Otto still had resources. While serving time at Moundsville, he hired a lawyer and thus was born a case before the U.S. Supreme Court at its 1876 October term, entitled “Ex Parte Karstendiek.”

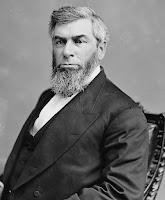

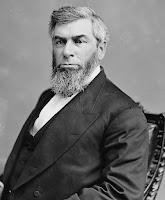

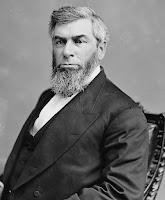

His lawyer argued that the decision to send Otto and the others out of Louisiana was not authorized by law and should be voided. The U.S. Solicitor General countered that when no suitable prison facilities could be found in the state where the felony occurred, the government was justified in sending prisoners elsewhere. With Chief Justice Morrison Waite, right, writing the decision, the high court concluded that: “So long as the State [West Virginia] permits him to remain in its prison as the prisoner of the United States, and does not object to his detention by its officers, he is rightfully detained on custody under a sentence lawfully passed.” Otto spent his 16 months a long way from his family.

His lawyer argued that the decision to send Otto and the others out of Louisiana was not authorized by law and should be voided. The U.S. Solicitor General countered that when no suitable prison facilities could be found in the state where the felony occurred, the government was justified in sending prisoners elsewhere. With Chief Justice Morrison Waite, right, writing the decision, the high court concluded that: “So long as the State [West Virginia] permits him to remain in its prison as the prisoner of the United States, and does not object to his detention by its officers, he is rightfully detained on custody under a sentence lawfully passed.” Otto spent his 16 months a long way from his family.

Judge Waite had not seen the last of Otto Karstendiek. In 1877 the whiskey man, now free, was back before the Supreme Court. This time he was objecting to the seizure of his liquor stocks and their forfeiture to the federal government. In a case entitled “United States v. Two Hundred Barrels of Whiskey,” Otto demanded that the liquor be returned to him. His lawyer spun a convoluted argument about conflicting federal rules that required immediate release of the whiskey. Once again Waite wrote the opinion. Lower federal courts had upheld such forfeitures. The Supreme Court affirmed them. Otto went home without his 200 barrels.

Unlike other liquor houses whose owners were implicated in the Whiskey Ring, Otto’s business did not disappear. While his father was incarcerated, his eldest son, Henry S. Karstendiek, shown here, took over running what remained of his father’s business. The name was changed to “O.H. Karstendiek Son Company.” Otto’s brother John also began clerking in the establishment that remained on Tchoupoulas Street. Henry, along with younger members of the family, continued living with their disgraced father. The last directory entry for the Karstendiek liquor house was 1879. In the 1880 census Otto gave his occupation as “grocer.”

Unlike other liquor houses whose owners were implicated in the Whiskey Ring, Otto’s business did not disappear. While his father was incarcerated, his eldest son, Henry S. Karstendiek, shown here, took over running what remained of his father’s business. The name was changed to “O.H. Karstendiek Son Company.” Otto’s brother John also began clerking in the establishment that remained on Tchoupoulas Street. Henry, along with younger members of the family, continued living with their disgraced father. The last directory entry for the Karstendiek liquor house was 1879. In the 1880 census Otto gave his occupation as “grocer.”

Otto died on April 21, 1883, quite unusually exactly 60 years to the day of his birth. His funeral was private, conducted at John’s home with only friends of the family invited to attend. Then the deceased was taken to the site of the cast iron crypt in Lafayette Cemetery #1, said to have been brought from Germany by Otto after a visit to the Continent.

One of only sixteen iron “houses of the dead,” in all New Orleans and a tourist attraction because of Anne Rice’s vampire novels, the structure in 2016 badly needed repairs estimated at from $50,000 to $70,000. A fundraiser featured people in costumes and a visit by two of Otto’s descendants from Texas. They told a reporter they had no idea who actually was buried inside and hoped the restoration would reveal some answers. When the work began we can assume that, unlike Rice’s Lestat, Otto Karstendiek did not come walking out.

Notes: This post was prompted from seeing a Karstendiek letterhead on a note written in German to the manager of the Menger Hotel in New Orleans not long after the Civil War. The oddness of the piece, on sale on eBay, caused me to do some research on Otto. It led me to the tragic fire, the Whiskey Ring, and other events in this whiskey man’s life. This story emerged.

Fans of the movie version of Anne Rice’s “Interview with the Vampire” will recognize at right the New Orleans above-ground tomb of her blood-sucking hero, Lestat. When visiting Lafayette Cemetery #1, tourists often seek out the cast-iron crypt and wonder who actually is interred there. It is Otto Henry Karstendieck, a liquor dealer whose life, like Lestat’s, contained more than sufficient horror, death and deception to make his tale worth telling. Otto’s story, in contrast to Rice’s, is non-fiction.

Fans of the movie version of Anne Rice’s “Interview with the Vampire” will recognize at right the New Orleans above-ground tomb of her blood-sucking hero, Lestat. When visiting Lafayette Cemetery #1, tourists often seek out the cast-iron crypt and wonder who actually is interred there. It is Otto Henry Karstendieck, a liquor dealer whose life, like Lestat’s, contained more than sufficient horror, death and deception to make his tale worth telling. Otto’s story, in contrast to Rice’s, is non-fiction.

Otto was born on April 21, 1823, in Bremen, Germany, the son of Heinrich and Anna Metta Karstendiek. Of his early life and education the record is blank, as well as is the exact date of his coming to America, apparently around 1850. What propelled him to New Orleans similarly is obscure. The first public record I can find is 1856 when he was 33 years old and New Orleans was a booming city, shown below. In May of that year Otto married Delia Cecelia Salomon, whose claim to fame was being the sister of the first “Rex” of the Mardi Gras parade. Over the next eight years the couple would have five children, two daughters and three sons.

Meanwhile Otto was demonstrating his abilities as a liquor and wine dealer, claiming his liquor house origin as 1850. From his Tchoupoulas Street headquarters in uptown New Orleans close to the Mississippi River, as early as 1853 he was advertising in a wide area beyond Louisiana. A Galveston newspaper ad declared Karstendiek & Company an importer of European brandies and wines as well as “Dealers in all kinds of domestic liquors….” By the end of the decade Otto was doing business from two warehouses, each four stories high, a block long and filled with liquor.

Meanwhile Otto was demonstrating his abilities as a liquor and wine dealer, claiming his liquor house origin as 1850. From his Tchoupoulas Street headquarters in uptown New Orleans close to the Mississippi River, as early as 1853 he was advertising in a wide area beyond Louisiana. A Galveston newspaper ad declared Karstendiek & Company an importer of European brandies and wines as well as “Dealers in all kinds of domestic liquors….” By the end of the decade Otto was doing business from two warehouses, each four stories high, a block long and filled with liquor.

On Saturday, October 13, 1860, tragedy struck. About 8 p.m. a large fire of undetermined origin broke out in one Karstendiek warehouse. Soon the structure was engulfed in flames from the ground floor to the roof, imperiling the second warehouse. When the fire reached the top floor where considerable liquor was stored, a tremendous explosion occurred, destroying both warehouses and spreading the fire to adjoining structures.

On Saturday, October 13, 1860, tragedy struck. About 8 p.m. a large fire of undetermined origin broke out in one Karstendiek warehouse. Soon the structure was engulfed in flames from the ground floor to the roof, imperiling the second warehouse. When the fire reached the top floor where considerable liquor was stored, a tremendous explosion occurred, destroying both warehouses and spreading the fire to adjoining structures.

The New Orleans Picayune reported: “No battlefield, no steamboat explosion could exceed the horror of the scene. There under the enormous mass of smoking ruins, thirty or forty men lay buried.” Chief among them were members of New Orleans volunteer fire companies that had responded to the alarm and were pour water on the first warehouse. The paper listed names and units of men pulled dead, dying or injured in the explosion. Among those who barely escaped was the New Orleans chief of police. Rescue efforts were hampered by the intense heat of the fire. “Many, many more remained buried under the ruins,as we left the scene. Two had been heard to speak, but could not be reached and, horrible to relate, they stated that the fire was burning the timbers underneath, and gaining upon them,” the newspaper reported.

Otto does not seem to have been on the premises when the fire occurred. While he sustained the loss of his buildings and some stock, quantities of the whiskey he was storing reputedly were owned by second parties. Although I can find no information on the total death count or monetary loss the latter would be the equivalent today of millions.

It is likely that among the dead and injured were Karstendiek & Co. employeeswhose deaths Otto would have mourned as he attempted to collect on his insurance and rebuild his business at a new location on Tchoupoulas Street. He continued to advertise widely as: “Dealers in Old Bourbon, Rye. Monogahela. Tennessee white, Roblnson county, White Wheat, and common whiskey.”

The advent of the Civil War proved a boon to Otto. Although initially revenues in the city fell with Union occupation, a “welfare state” was created by federal authorities to alleviate “the deplorable state of destitution and hunger of the mechanics and working classes of the city.” It was paid for by a special tax on the wealthy and businesses. Revenues allowed the military government to employ 2,000 men daily to clean up the city. The levy also generated relief payments to 11,000 families, most of whom were Irish and German. Moreover, Union forces in New Orleans and vicinity grew to 17,800. The customer base for Otto’s liquor swelled.

The end of the Civil War brought a double setback. After the birth of their fifth child, the health of Otto’s wife Delia declined and after just nine years of marriage in November 1865 she died at the age of 29. Her husband was left with the sole care of five children, the oldest nine, the youngest a toddler. Five years later Otto remarried. His new spouse was Ella Lavernia Stoddard from Albany, New York. They would have one son.

The second blow was the reduced revenues Otto was facing in New Orleans during Reconstruction. Gone were the subsidies for workers and the payroll of a large standing army. The customer base for Karstendiek & Company dwindled sharply. Otto decided to “go to the dark side.” He joined in what came to be known as “The Whiskey Ring,” a massive scheme to cheat the federal government of millions of dollars in liquor revenues. Hatched in 1871 by a top Grant Administration revenue official in St. Louis, the conspiracy had its tentacles in Chicago, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and stretched south to New Orleans.

There President Grant had appointed his wife’s brother-in -law, Col. James B. Case, as collector of customs for the port. Casey was quick to see the ease and financial possibilities of skimming off illicit cash from liquor taxes. He recruited a handful of New Orleans distillers and liquor dealers to assist him in the scheme. Among them was Otto Karstendiek.

In addition to selling whiskey and other alcoholic products at wholesale and retail,

Otto was a “rectifier,” that is, someone blending raw whiskeys on his premises in order to achieve a specific color, smoothness and taste. Because the blending added value to the product, rectifiers were required to keep detailed records and were taxed on the amount of product blended. By variety of mean, from corrupt federal “gaugers” who falsified production or the use of fraudulent revenue stamps, the U.S. Treasury was cheated out of millions.

The Whiskey Ring came to abrupt halt on May 10, 1875, when U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin Bristow, working without the knowledge of President Grant, broke up the tightly connected and politically powerful cabal. He used secret agents from outside the Treasury Department to conduct a series of raids across the country on May 10, 1875. Among those arrested was Otto Karstendiek.

The Whiskey Ring came to abrupt halt on May 10, 1875, when U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin Bristow, working without the knowledge of President Grant, broke up the tightly connected and politically powerful cabal. He used secret agents from outside the Treasury Department to conduct a series of raids across the country on May 10, 1875. Among those arrested was Otto Karstendiek.

Otto and his co-conspirators did not come to trial until almost a full year after the raid. In the interim the German whiskey man had suffered another heartbreaking loss. Ella, his wife of just four years, died in September 1875, leaving him with a sixth motherless child. At his trial in the U.S. Circuit for the District of Louisiana in May 1875, Otto and five of his co-conspirators were found guilty and sentenced. James Casey was not among them. The prisoners were fined from $1,000 to $6,000 and sentenced to prison variably from six to sixteen months. Otto was assessed $1000 and maximum prison time.

All six were sent to the State Penitentiary at Moundsville, West Virginia, shown here, more than 1,000 miles from Otto’s New Orleans home. He must have been anguished at serving time so far from his children, now to be looked after by others. Although his liquor house was shut briefly as the result of his folly, Otto still had resources. While serving time at Moundsville, he hired a lawyer and thus was born a case before the U.S. Supreme Court at its 1876 October term, entitled “Ex Parte Karstendiek.”

All six were sent to the State Penitentiary at Moundsville, West Virginia, shown here, more than 1,000 miles from Otto’s New Orleans home. He must have been anguished at serving time so far from his children, now to be looked after by others. Although his liquor house was shut briefly as the result of his folly, Otto still had resources. While serving time at Moundsville, he hired a lawyer and thus was born a case before the U.S. Supreme Court at its 1876 October term, entitled “Ex Parte Karstendiek.”

His lawyer argued that the decision to send Otto and the others out of Louisiana was not authorized by law and should be voided. The U.S. Solicitor General countered that when no suitable prison facilities could be found in the state where the felony occurred, the government was justified in sending prisoners elsewhere. With Chief Justice Morrison Waite, right, writing the decision, the high court concluded that: “So long as the State [West Virginia] permits him to remain in its prison as the prisoner of the United States, and does not object to his detention by its officers, he is rightfully detained on custody under a sentence lawfully passed.” Otto spent his 16 months a long way from his family.

His lawyer argued that the decision to send Otto and the others out of Louisiana was not authorized by law and should be voided. The U.S. Solicitor General countered that when no suitable prison facilities could be found in the state where the felony occurred, the government was justified in sending prisoners elsewhere. With Chief Justice Morrison Waite, right, writing the decision, the high court concluded that: “So long as the State [West Virginia] permits him to remain in its prison as the prisoner of the United States, and does not object to his detention by its officers, he is rightfully detained on custody under a sentence lawfully passed.” Otto spent his 16 months a long way from his family.

Judge Waite had not seen the last of Otto Karstendiek. In 1877 the whiskey man, now free, was back before the Supreme Court. This time he was objecting to the seizure of his liquor stocks and their forfeiture to the federal government. In a case entitled “United States v. Two Hundred Barrels of Whiskey,” Otto demanded that the liquor be returned to him. His lawyer spun a convoluted argument about conflicting federal rules that required immediate release of the whiskey. Once again Waite wrote the opinion. Lower federal courts had upheld such forfeitures. The Supreme Court affirmed them. Otto went home without his 200 barrels.

Unlike other liquor houses whose owners were implicated in the Whiskey Ring, Otto’s business did not disappear. While his father was incarcerated, his eldest son, Henry S. Karstendiek, shown here, took over running what remained of his father’s business. The name was changed to “O.H. Karstendiek Son Company.” Otto’s brother John also began clerking in the establishment that remained on Tchoupoulas Street. Henry, along with younger members of the family, continued living with their disgraced father. The last directory entry for the Karstendiek liquor house was 1879. In the 1880 census Otto gave his occupation as “grocer.”

Unlike other liquor houses whose owners were implicated in the Whiskey Ring, Otto’s business did not disappear. While his father was incarcerated, his eldest son, Henry S. Karstendiek, shown here, took over running what remained of his father’s business. The name was changed to “O.H. Karstendiek Son Company.” Otto’s brother John also began clerking in the establishment that remained on Tchoupoulas Street. Henry, along with younger members of the family, continued living with their disgraced father. The last directory entry for the Karstendiek liquor house was 1879. In the 1880 census Otto gave his occupation as “grocer.”

Otto died on April 21, 1883, quite unusually exactly 60 years to the day of his birth. His funeral was private, conducted at John’s home with only friends of the family invited to attend. Then the deceased was taken to the site of the cast iron crypt in Lafayette Cemetery #1, said to have been brought from Germany by Otto after a visit to the Continent.

One of only sixteen iron “houses of the dead,” in all New Orleans and a tourist attraction because of Anne Rice’s vampire novels, the structure in 2016 badly needed repairs estimated at from $50,000 to $70,000. A fundraiser featured people in costumes and a visit by two of Otto’s descendants from Texas. They told a reporter they had no idea who actually was buried inside and hoped the restoration would reveal some answers. When the work began we can assume that, unlike Rice’s Lestat, Otto Karstendiek did not come walking out.

Notes: This post was prompted from seeing a Karstendiek letterhead on a note written in German to the manager of the Menger Hotel in New Orleans not long after the Civil War. The oddness of the piece, on sale on eBay, caused me to do some research on Otto. It led me to the tragic fire, the Whiskey Ring, and other events in this whiskey man’s life. This story emerged.

For this 900th post I have chosen the story of Jeremiah Joseph O’Connor of Elmira, New York. Although his story may lack the drama of other whiskey men’s lives, O’Connor epitomizes those individuals who immigrated to the United States, found a career in the liquor trade and went on to help build their communities — and by doing so, America. O’Connor was, in other words, a model whiskey man.

For this 900th post I have chosen the story of Jeremiah Joseph O’Connor of Elmira, New York. Although his story may lack the drama of other whiskey men’s lives, O’Connor epitomizes those individuals who immigrated to the United States, found a career in the liquor trade and went on to help build their communities — and by doing so, America. O’Connor was, in other words, a model whiskey man. Intelligent and ambitious, O’Conner’s early career included teaching in a Catholic grade school, eventually being raised to principal. His reputed talent as a educator brought him to the attention of the upwardly mobile Irish-American community and other residents. He also found a bride in Elmira, wedding Mary Purcell, a woman of Irish immigrant parents, shown here in middle age. At the time of their 1871 nuptials, according to census data, Jerry was 27 and Mary was 17. Over the next 17 years the couple would have eight children, all of whom seem to have lived to maturity.

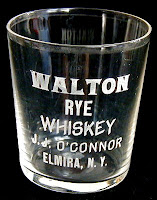

Intelligent and ambitious, O’Conner’s early career included teaching in a Catholic grade school, eventually being raised to principal. His reputed talent as a educator brought him to the attention of the upwardly mobile Irish-American community and other residents. He also found a bride in Elmira, wedding Mary Purcell, a woman of Irish immigrant parents, shown here in middle age. At the time of their 1871 nuptials, according to census data, Jerry was 27 and Mary was 17. Over the next 17 years the couple would have eight children, all of whom seem to have lived to maturity. Like many whiskey wholesalers O’Connor marketed his own proprietary brand of whiskey, called “Walton.” This liquor would have been supplied to him by a nearby distillery to a recipe he dictated or, more likely, blended on his premises. A practice in the trade was to reward special customers with items such as shot glasses advertising such house brands. O’Connor’s giveaway was particularly stylish. As business flourished he relocated to larger quarters at 414-416 Carroll Street.

Like many whiskey wholesalers O’Connor marketed his own proprietary brand of whiskey, called “Walton.” This liquor would have been supplied to him by a nearby distillery to a recipe he dictated or, more likely, blended on his premises. A practice in the trade was to reward special customers with items such as shot glasses advertising such house brands. O’Connor’s giveaway was particularly stylish. As business flourished he relocated to larger quarters at 414-416 Carroll Street. In the meantime O’Connor’s ability and accomplishments had advanced him to major roles in the Democratic Party. Following an appointment to the Elmira Board of Heath for two years, he was put forward as the Democratic candidate for the New York General Assembly in 1883. He won and served two terms, during which his talent as “a public speaker of no mean ability” brought him notice. At the 1885 state Democrtic convention, O’Connor was chosen to place the party candidate for governor in nomination, a singular tribute to his eloquence.

In the meantime O’Connor’s ability and accomplishments had advanced him to major roles in the Democratic Party. Following an appointment to the Elmira Board of Heath for two years, he was put forward as the Democratic candidate for the New York General Assembly in 1883. He won and served two terms, during which his talent as “a public speaker of no mean ability” brought him notice. At the 1885 state Democrtic convention, O’Connor was chosen to place the party candidate for governor in nomination, a singular tribute to his eloquence. Financial interests increasingly called O’Connor to New York City. There in 1910, he fell down the steps of a Manhattan subway and was severely injured. When the damage proved permanently disabling, he directed the 1912 incorporation of the Jeremiah J. O’Connor liquor company. As directors he appointed his wife Mary and one of his sons, 23-year-old Charles Borromeo O’Connor. Aware that his injuries might lead to complete incapacity or death, Jerry wisely had looked to the future. It was not long in coming. He died on November 23, 1913, at the age of 68 and was buried in Elmira’s St. Peter and Paul Cemetery. His headstone is shown here.

Financial interests increasingly called O’Connor to New York City. There in 1910, he fell down the steps of a Manhattan subway and was severely injured. When the damage proved permanently disabling, he directed the 1912 incorporation of the Jeremiah J. O’Connor liquor company. As directors he appointed his wife Mary and one of his sons, 23-year-old Charles Borromeo O’Connor. Aware that his injuries might lead to complete incapacity or death, Jerry wisely had looked to the future. It was not long in coming. He died on November 23, 1913, at the age of 68 and was buried in Elmira’s St. Peter and Paul Cemetery. His headstone is shown here.

Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey tells

Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey tells

The post

The post