The Kreielsheimers’ “Northwest Passage” to Prosperity

Immigrants from Germany, the Kreielsheimer brothers — Simon, Jacob and Max — early saw the American Northwest as fertile grounds for selling whiskey and cultivated a customer base that encompassed the State of Washington, Idaho and even north to Alaska. Cited as equal to any found in the largest cities in America, through their pioneering liquor house the brothers achieved a remarkable run of 27 prosperous years.

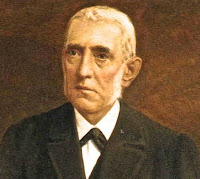

Born into a Lutheran family in Offenburg, Baden-Wurtemberg, Germany, the brothers were the only offspring of Hannah and Lazarus Kreielsheimer. The eldest was Simon, shown here, born in 1859, followed by Jacob in 1863 and Max in 1869. In 1875, Simon, at 16 nearing draft age for the Prussian army, left his home for the United States, bringing with him his 12 year old brother, Jacob. My assumption is that initially the pair lodged with relatives living in the vicinity of New York City.

Born into a Lutheran family in Offenburg, Baden-Wurtemberg, Germany, the brothers were the only offspring of Hannah and Lazarus Kreielsheimer. The eldest was Simon, shown here, born in 1859, followed by Jacob in 1863 and Max in 1869. In 1875, Simon, at 16 nearing draft age for the Prussian army, left his home for the United States, bringing with him his 12 year old brother, Jacob. My assumption is that initially the pair lodged with relatives living in the vicinity of New York City.

By 1880, Simon, possibly drawn to California by gold strikes, was living in San Francisco and employed as a clerk for the E. Goslinsky Company, a tobacco importer and cigar manufacturer. Meanwhile Jacob, having learned the upholstery trade, was working in and around New York. Sometime in the mid decade, Goslinsky sent Simon to Seattle, then still part of the Territory of Washington — not yet admitted to the Union.

In Seattle the oldest Kreielsheimer saw an excellent opportunity for a quality liquor and wine wholesaler serving the Northeast and beyond. Simon summoned his brothers to join him. Chucking his upholstery work, Jacob answered the call. Just 18 and still in Germany, Max boarded the SS Imperator and headed for America. Both arrived in 1887, the same year that the liquor house of Kreielsheimer Bros. was born. At the outset Simon and Jacob were the executives. Shown here in maturity, Max initially was listed as a “clerk.”

In Seattle the oldest Kreielsheimer saw an excellent opportunity for a quality liquor and wine wholesaler serving the Northeast and beyond. Simon summoned his brothers to join him. Chucking his upholstery work, Jacob answered the call. Just 18 and still in Germany, Max boarded the SS Imperator and headed for America. Both arrived in 1887, the same year that the liquor house of Kreielsheimer Bros. was born. At the outset Simon and Jacob were the executives. Shown here in maturity, Max initially was listed as a “clerk.”

Their first address was 323 Commercial Street but found their business growing so rapidly that within two years they had moved to larger quarters at 309-311 Commercial. By 1895 those accommodations had proven too small and the brothers moved a final time to the newly constructed Hotaling Block at 209 First Avenue, occupying a four story building, 30 by 111 feet in size. A photograph of their venue from around 1900 shows the highly decorated structure with a delivery wagon parked out front and a crowd of well-dressed men. My assumption is that the Kreielsheimers are among them.

Their first address was 323 Commercial Street but found their business growing so rapidly that within two years they had moved to larger quarters at 309-311 Commercial. By 1895 those accommodations had proven too small and the brothers moved a final time to the newly constructed Hotaling Block at 209 First Avenue, occupying a four story building, 30 by 111 feet in size. A photograph of their venue from around 1900 shows the highly decorated structure with a delivery wagon parked out front and a crowd of well-dressed men. My assumption is that the Kreielsheimers are among them.

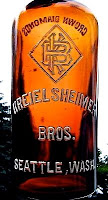

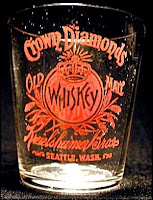

Those quarters provided ample room for the Kreielsheimers to store an extensive stock of liquor, including nationally known brands. They also engaged in a “rectifying” operation blending two proprietary whiskeys on site, “Old Line Whiskey” and their flagship “Crown Diamonds Malt Whiskey.” For their wholesale customers they were selling whiskey by the barrel as well as in embossed glass bottles, in clear and amber, bearing a company monogram.

Those quarters provided ample room for the Kreielsheimers to store an extensive stock of liquor, including nationally known brands. They also engaged in a “rectifying” operation blending two proprietary whiskeys on site, “Old Line Whiskey” and their flagship “Crown Diamonds Malt Whiskey.” For their wholesale customers they were selling whiskey by the barrel as well as in embossed glass bottles, in clear and amber, bearing a company monogram.

The brothers also expanded their operations throughout the State of Washington and beyond to other parts of the Northwest, including Idaho and Alaska. Below is a photograph of a band lined up in front of the Kreielsheimer Bros. headquarters in Juneau. Additionally, the company maintained quarters in Room 507 of Spokane’s Fraternal Building, 48-50 First Street in San Francisco, and 912-916 Sycamore Street in Cincinnati. This last office likely was devoted to purchasing and sending supplies of whiskey to Seattle from the many distillers and brokers in the Ohio city. “The arrangement of the offices and the whole establishment is fully equal to any found in the largest cities in America,” boasted one Seattle publication.”

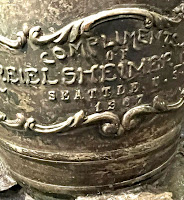

Another claim to whiskey fame derives from the unique, and relatively expensive, advertising items with which the brothers gifted their wholesale customers. Worth attention is a metal tray with individual plates shaped like clam shells. In the center is a barrel-like object with the inscription “Compliments of the Kreielsheimer Bros…Seattle U.S…1907.” I believe this tray was meant to carry small bites of free food for the bar crowd. The barrel held toothpicks used for spearing the delicacies. The underside of the tray reveals round emblems advertising the brothers’ brands. Note that one has been lost over time.

Another claim to whiskey fame derives from the unique, and relatively expensive, advertising items with which the brothers gifted their wholesale customers. Worth attention is a metal tray with individual plates shaped like clam shells. In the center is a barrel-like object with the inscription “Compliments of the Kreielsheimer Bros…Seattle U.S…1907.” I believe this tray was meant to carry small bites of free food for the bar crowd. The barrel held toothpicks used for spearing the delicacies. The underside of the tray reveals round emblems advertising the brothers’ brands. Note that one has been lost over time.

Still another Kreielsheimer giveaway item was a ladle dated 1906. Like the tray this item would have been given to upscale saloons, restaurants and hotels using the brothers’ brands. The handle bears images of grapes, wheat and corn, indicating that the punch bowl for which it was intended might hold wine, rum or whiskey. A monogram of the firm initials is the largest feature as well as the company name spelled vertically down the shaft. This ladle also would have been a relatively expensive gift to customers.

Still another Kreielsheimer giveaway item was a ladle dated 1906. Like the tray this item would have been given to upscale saloons, restaurants and hotels using the brothers’ brands. The handle bears images of grapes, wheat and corn, indicating that the punch bowl for which it was intended might hold wine, rum or whiskey. A monogram of the firm initials is the largest feature as well as the company name spelled vertically down the shaft. This ladle also would have been a relatively expensive gift to customers.

For most of their company life the batchelor brothers not only worked together but lived together. They also seemed to move frequently. The 1890 Seattle directory lists them rooming one year at Eureka House Hotel. One author lists that residence among Seattle’s hotels that harbored brothels accommodating as many as twenty Japanese women. After one year the Kreielsheimers had moved to other, possibly less lively, quarters. The three found a permanent home in 1908 when the Arctic Club opened in Seattle’s posh Morrison Hotel. This was a fraternal men’s club for businessmen with Klondike Gold Rush or other Alaska experience. With their pioneering work to sell liquor in Juneau the Kreielsheimers were welcomed as members. They reciprocated by selling liquor in specially designed bottles for the club.

For most of their company life the batchelor brothers not only worked together but lived together. They also seemed to move frequently. The 1890 Seattle directory lists them rooming one year at Eureka House Hotel. One author lists that residence among Seattle’s hotels that harbored brothels accommodating as many as twenty Japanese women. After one year the Kreielsheimers had moved to other, possibly less lively, quarters. The three found a permanent home in 1908 when the Arctic Club opened in Seattle’s posh Morrison Hotel. This was a fraternal men’s club for businessmen with Klondike Gold Rush or other Alaska experience. With their pioneering work to sell liquor in Juneau the Kreielsheimers were welcomed as members. They reciprocated by selling liquor in specially designed bottles for the club.

The year 1915 proved pivotal for the brothers. In March 1915, Jacob died at the age of 51. He was buried at the Hills of Eternity section of Seattle’s Mt. Pleasant Cemetery. When Washington voters passed statewide prohibition, the majority of voters in Seattle had voted against it. The law went into effect in 1915; Seattle was obliged to comply. After 27 years of successful operation the two remaining Kreielsheimers were forced to shut down their wholesale liquor house.

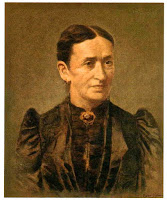

While continuing to maintain the name of their company as an investment firm, Simon and Max branched out into new enterprises. Simon became president of the Kodiak Fisheries Co. and the Northeast Leather Company. Max was secretary-treasurer of the latter. In 1926 they both still lived at the Arctic Club. In a surprise move, at the age of 57 Max got married. His bride was Olivia Agnes Thornton, 45, a Seattle milliner, shown here. She apparently had a previous marriage and a young son. They exchanged vows in Nanaimo, British Columbia, just over the border from Washington State.

While continuing to maintain the name of their company as an investment firm, Simon and Max branched out into new enterprises. Simon became president of the Kodiak Fisheries Co. and the Northeast Leather Company. Max was secretary-treasurer of the latter. In 1926 they both still lived at the Arctic Club. In a surprise move, at the age of 57 Max got married. His bride was Olivia Agnes Thornton, 45, a Seattle milliner, shown here. She apparently had a previous marriage and a young son. They exchanged vows in Nanaimo, British Columbia, just over the border from Washington State.

In December 1926, Simon, still a bachelor at 67, died and was interred next to Jacob. Max followed eleven years later and was buried adjacent to his brothers A monument marks the spot where the trio lay. As they had bonded together in life they are join in their final resting place.

Note: This post was drawn from a number of sources. Key among them were John Thomas’s 1998 “Whiskey Bottles and Liquor Containers from The State of Washington,” Alfred D. Bowen’s 1900 “Seattle and the Orient” souvenir pamphlet, and genealogy sites.