No “Little Town Blues” for Distiller Fred Weaver

Containing a substantial scattering of small towns, Daughin County is located in Pennsylvania coal country. There Fred Weaver spent much of his working life distilling and selling whiskey, merchandising his liquor in those limited surroundings with a flair that matched “Big City” houses. Devoting an entire page of memorials to Weaver’s career, the local newspaper declared: “He met with marked success in all his undertakings….”

Containing a substantial scattering of small towns, Daughin County is located in Pennsylvania coal country. There Fred Weaver spent much of his working life distilling and selling whiskey, merchandising his liquor in those limited surroundings with a flair that matched “Big City” houses. Devoting an entire page of memorials to Weaver’s career, the local newspaper declared: “He met with marked success in all his undertakings….”

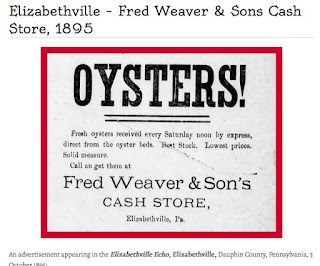

Weaver was born in 1830 in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, the son of Frederick Weaver, a blacksmith who later moved his family to Pottsville where the son, working beside his father, learned the smithy’s trade. From there the young man gravitated to Daughin County, engaged as a carriage builder in Berrysburg (pop. 426) and eventually opening a general merchandise store there. Apparently finding that hamlet too small, Weaver moved the business a short distance to Elizabethville (pop. 1,218). At Market and Main Streets he constructed a building that became his headquarters. Eventually that building became known as the Fred Weaver & Son’s Cash Store.

|

| Main Street, Elizabethville |

Sales of liquor from his Elizabethville store apparently convinced Weaver of the profits to be achieved from not just selling whiskey but producing it. In 1875 at the age of 45, Weaver opened a distillery there that in time became Weaver & Son Company as earlier partners departed. It was registered as Distillery No. 2. 9th District of Pennsylvania. A label for his whiskey, shown left, provides an accurate picture of the facility. Note the adjacent railroad siding. Weaver’s liquor from Daughin County could be shipped throughout Pennsylvania and other adjacent states.

Sales of liquor from his Elizabethville store apparently convinced Weaver of the profits to be achieved from not just selling whiskey but producing it. In 1875 at the age of 45, Weaver opened a distillery there that in time became Weaver & Son Company as earlier partners departed. It was registered as Distillery No. 2. 9th District of Pennsylvania. A label for his whiskey, shown left, provides an accurate picture of the facility. Note the adjacent railroad siding. Weaver’s liquor from Daughin County could be shipped throughout Pennsylvania and other adjacent states.

To his wholesale customers, Weaver sold his whiskey in a variety of ceramic jugs, each holding a gallon or two of his whiskey. Shown right is a vessel with a brown glaze and a blue cobalt script label, a rather unique format. Below are company jugs with a more traditional branding. Those would have been sold to wholesale customers who would pour them into smaller containers for serving across the bar.

To his wholesale customers, Weaver sold his whiskey in a variety of ceramic jugs, each holding a gallon or two of his whiskey. Shown right is a vessel with a brown glaze and a blue cobalt script label, a rather unique format. Below are company jugs with a more traditional branding. Those would have been sold to wholesale customers who would pour them into smaller containers for serving across the bar.

The distillery featured several “house” brands, including “That Weaver Whiskey,” “Silver Spring Whiskey,” and “Copper Double Distilled Rye.” These were marketed to retail customers from Weaver’s Elizabethville general store in flasks and quart-sized glass bottles as shown here and below. The labels were professionally designed and executed, in no way inferior in designs originating in Philadelphia or Pittsburgh.

The distillery featured several “house” brands, including “That Weaver Whiskey,” “Silver Spring Whiskey,” and “Copper Double Distilled Rye.” These were marketed to retail customers from Weaver’s Elizabethville general store in flasks and quart-sized glass bottles as shown here and below. The labels were professionally designed and executed, in no way inferior in designs originating in Philadelphia or Pittsburgh.

Another “big city” attribute of Weaver’s were the shot glasses he gave away to his wholesale and retail customers. As with his other merchsndise, these were well designed. He also was willing to spend extra for the white embossing that graced many of them, as shown below.

Profits from whiskey sales fueled other Weaver enterprises. These included the firm of Weaver & Wallace, an enterprise that controlled a tri-weekly freight line that ran between Daughin County coal towns to Philadelphia. To service this transport activity, Weaver built the first railroad stations at Lykens (pop. 2,450) and Williamstown (pop. 2,344) and a terminal freight station in Philadelphia. He also served for many years as a director of the Bank of Millersburg (pop. 1,527) and the Bank of Lykens. Shown below are the railroad station and Lykens bank.

Even as Weaver approached his late 60s, he continued to be active in running the distillery, seemingly although aging “full of life and vigor.” In November 1898, however, after attending a funeral for a family friend Weaver told his wife he was not feeling well. According to the Elizabethville Echo newspaper: “…Upon returning home he at once repaired to the radiator, with the remark that his feet were cold…Scarcely a dozen words were exchanged and barely ten minutes had elapsed after entering when he was seen falling from his chair. He was dead!” The cause of death apparently was a massive stroke.

Said to be a regular member of the St. Johns Evangelical Lutheran Church in Elizabethville, Weaver was buried from there after services conducted by Pastor Pflueger. Interment was in Maple Grove Cemetery. His widow, Catherine, would join him 16 years later.

The Elizabethville Echo memorial page devoted to Fred Weaver contains this eulogy, summarizing his life and achievements: “In the death of Mr. Weaver [a] marked personality and excellent character passes from the stage of action. He had been a citizen of this town for nigh on thirty-five years, and there is not one who would not testify to his generous traits of character, his commendable enterprise as a citizen and his excellent social bearings.”

Note: Son Henry Weaver continued the operation of the Elizabethville distillery until at least until 1905 when withdrawals of liquor from company warehouses ceased to be recorded by Federal authorities. As shown above, glass and ceramic containers bearing the Weaver name continue to come to attention reminding subsequent generations of a Pennsylvania distiller who achieved distinction despite never straying from his small town roots.