Ladner Bros. Wrote a Tale of Four Cities

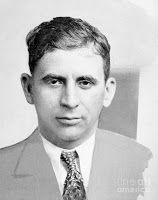

Brought to the United States from Germany in 1889 by their parents while they were still minors, Frank and Carl Ladner went on to create a wholesale and retail liquor enterprise that stretched from Montana to Illinois and produced a quantity of whiskey jugs that command significant prices from avid collectors. The brothers are pictured here in maturity, Frank, the eldest, on the left.

After arriving in America the family initially settled in St. Paul, Minnesota, where the father, Franz Henry, found employment. After six years, the Ladners moved in 1895 to nearby Red Wing, Minnesota, known for its quality potteries. There Frank with the help of Carl founded the Ladner Brothers Saloon and Wholesale Liquor Company on the city’s Main Street. The business apparently was a success. With local potteries doing a booming business at the time, many of their workers had a taste for alcohol.

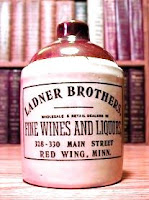

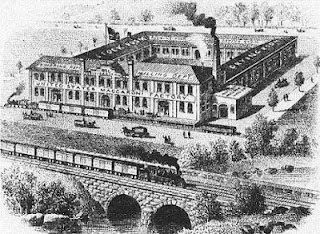

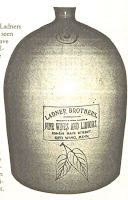

The Red Wing potteries also provided the Ladners with containers for their wholesale whiskey. As shown here, the jugs ranged in size from one to five gallons, all bearing similar labels. The Ladners were not distillers but were buying whiskey by the barrels, likely from distillers in Peoria and other Illinois locations, decanting them into smaller quantities and selling the product to saloons in Red Wing and the nearby Twin Cities, as well as pouring it over the bar in their adjoining saloon.

The Red Wing potteries also provided the Ladners with containers for their wholesale whiskey. As shown here, the jugs ranged in size from one to five gallons, all bearing similar labels. The Ladners were not distillers but were buying whiskey by the barrels, likely from distillers in Peoria and other Illinois locations, decanting them into smaller quantities and selling the product to saloons in Red Wing and the nearby Twin Cities, as well as pouring it over the bar in their adjoining saloon.

Meanwhile, both men were having personal lives. While still in St. Paul, at 19 Frank married. His bride was Ellen “Nellie” Cain, a woman born in Minnesota of Irish immigrant parents who was slightly older than he. During the next 10 years the couple would have six children. Then sorrow struck as Nellie died in November 1905. Left with children ranging in age from eleven years to a toddler, Frank remarried 18 months later. His bride was Anna Koester of Red Wing. They would go on to have four more children. Carl, age 22, in September 1899 married Mary Straiger, of German descent in Red Wing. They produced seven children.

For unexplained reasons, during the early 1900s the Ladners sold the liquor business to concentrate their energies on the success of their saloon. Five years later Carl ceded his interest in the Ladner saloon to Frank and headed 300 miles west up the Mississippi River to Aberdeen, South Dakota. There he opened a saloon and liquor store he called Aberdeen House. Indicating that his leaving Red Wing had been an amicable separation, Carl named Frank as a partner. A photograph exists of this establishment.

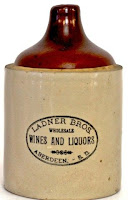

Moreover, Carl continued to buy his liquor containers from Red Wing. Selling at wholesale to Aberdeen saloons, he once again was buying “raw” whiskey from distilleries, delivered it to him in barrels by water and rail. He was decanting it into jugs and selling it to the saloons, restaurants and hotels of Aberdeen. As shown here the jugs ranged in size from a single gallon to two and five gallons.

Moreover, Carl continued to buy his liquor containers from Red Wing. Selling at wholesale to Aberdeen saloons, he once again was buying “raw” whiskey from distilleries, delivered it to him in barrels by water and rail. He was decanting it into jugs and selling it to the saloons, restaurants and hotels of Aberdeen. As shown here the jugs ranged in size from a single gallon to two and five gallons.

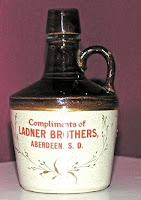

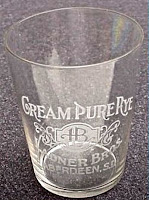

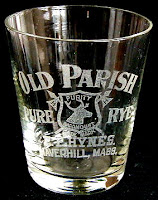

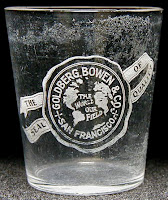

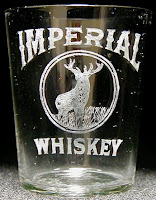

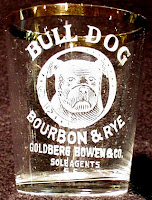

Like many liquor house proprietors, Carl was generous with his giveaways to his best customers. Below are to examples of gifted shot glasses. Note that like the sign on his saloon/liquor store, they advertise “Cream Pure Rye,” his house brand, likely blended on the premises. At the holidays he also gave away one-half pint decorative jugs of whiskey “Compliments of Ladner Brothers.”

Carl also was expanding the reach of the brothers’ liquor business, opening a branch office in Miles City, Montana, 360 miles west of Aberdeen, then still a “wild west” town. Advertising as “Ladner Bros. Wine and Liquor Merchants,” Carl installed an F. C. Schubring, a local of German heritage as his resident manager. Schubring, according to Miles City records, hired another Schubring, possibly his son, as a porter. Carl also is recorded operating a satellite saloon in James, South Dakota, a rowdy railroad hamlet 12 miles from Aberdeen.

Amid this expansion, the specter of prohibition was looming larger and larger. Local option laws bit by bit eliminated the ability of the Ladners to sell their liquor in surrounding communities. South Dakota went completely “dry” in 1917, followed by Montana in 1918. With foresight Carl had seen this strong movement in the upper Midwest to a ban on alcohol. He closed up the Ladner Brothers operations in Aberdeen and Miles City and moved to Chicago.

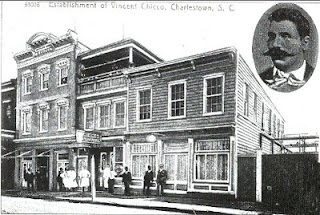

For a time Carl managed a Coca Cola plant there but “whiskey was in his blood” and with a friend from Red Wing days he established a new Ladner Brothers liquor house and cafe in The Windy City. Located at 207 West Madison Street, as shown above, it featured large signs, including one in neon, advertising the house brand, “Cohasset Punch.”

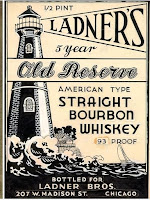

The company’s flagship whiskey now became “Ladner’s Old Reserve.” No longer was Carl mixing up whatever whiskey he could buy on the open market and selling it in generic jugs. This new enterprise allowed the Ladners to arrange for a distillery to prepare whiskey from a Ladner recipe and bottle it with a proprietary label. Below is a photo of the interior of the Chicago establishment, showing the bar and plenty of Old Reserve on the shelves. That is Carl Ladner standing far right. This profitable enterprise came to an end in 1920 with National Prohibition.

The company’s flagship whiskey now became “Ladner’s Old Reserve.” No longer was Carl mixing up whatever whiskey he could buy on the open market and selling it in generic jugs. This new enterprise allowed the Ladners to arrange for a distillery to prepare whiskey from a Ladner recipe and bottle it with a proprietary label. Below is a photo of the interior of the Chicago establishment, showing the bar and plenty of Old Reserve on the shelves. That is Carl Ladner standing far right. This profitable enterprise came to an end in 1920 with National Prohibition.

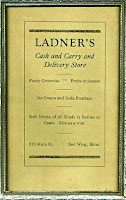

Meanwhile in Red Wing, Frank Ladner also was coping with the emerging “dry” era. With the coming of World War I and wartime restrictions on alcohol, he could see the demise of his liquor business. Moving to groceries, Frank’s saloon became “Ladner’s Cash and Carry and Delivery Store” featuring fancy goods, ice cream, a soda fountain, and “soft drinks of all kinds.” Nary a bottle of booze in sight.

Meanwhile in Red Wing, Frank Ladner also was coping with the emerging “dry” era. With the coming of World War I and wartime restrictions on alcohol, he could see the demise of his liquor business. Moving to groceries, Frank’s saloon became “Ladner’s Cash and Carry and Delivery Store” featuring fancy goods, ice cream, a soda fountain, and “soft drinks of all kinds.” Nary a bottle of booze in sight.

Back in Chicago Carl pivoted to the bottling trade, specializing in soft drinks and sparkling waters. He died in 1947 at age 70 and was buried Calvary Cemetery of suburban Evanston, Illinois. Frank lived to be 84, dying in 1956. He was buried in Red Wing’s Calvary Cemetery. Both men had seen the end of National Prohibition in 1934 but neither apparently was tempted once again to enter the whiskey trade that had sustained them and their families for so many years. We are the beneficiaries of their signature Red Wing pottery jugs and the story of an enterprising immigrant family.

Notes: This post has relied heavily for information on a 1995 publication entitled “The Red Wing Collectors Society Convention Supplement, Volume XI,” editor Chuck Drometer. A number of the photos used are from a Ladner Family Flickr site on the Internet. This material has been supplemented from other internet sources.