Why Did Neal Dow, “Father of Prohibition,” Buy Booze?

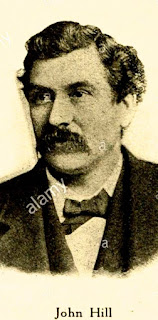

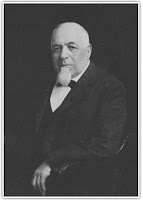

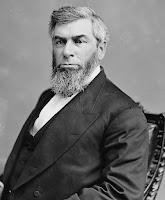

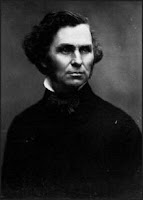

Claiming Neal Dow, shown here, as a “whiskey man’ may seem like a stretch. Dow has been cited as the “Father of Prohibition” and ran for President of the United States as the first Prohibitionist Party candidate. Consider, however, that in 1855 Dow illegally bought a supply of liquor valued at $56,000 in today’s dollar, stashed the supply at city hall in Portland, Maine, and as mayor held the key. His seeming duplicity incited a riot during which a man was killed.

Claiming Neal Dow, shown here, as a “whiskey man’ may seem like a stretch. Dow has been cited as the “Father of Prohibition” and ran for President of the United States as the first Prohibitionist Party candidate. Consider, however, that in 1855 Dow illegally bought a supply of liquor valued at $56,000 in today’s dollar, stashed the supply at city hall in Portland, Maine, and as mayor held the key. His seeming duplicity incited a riot during which a man was killed.

Dow was born in March 1804 into a prosperous Portland Quaker family. Although the youth demonstrated exceptional intelligence, his father, a man said to be of lofty morals, refused to send him to college, wary of the influences of college students of that day. As a result, Dow early joined his father in his tannery business and before long was made a partner. But hides were not his passion. Drink was. According to a biographer, even as a boy Dow strongly hated alcohol. At that time Americans drank three times as much as they do currently. Portland was a hotbed of legal and illegal drinking establishments, estimated at as many as 300 for a population of 21,000. The young man had found a cause worthy of his ambition.

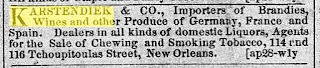

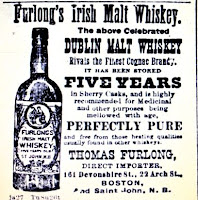

After co-founding the Maine Temperance Society in 1827 at the age of 23, Dow became a five foot, two inch, firebrand speaker against the evils of liquor. His orations were filled with horror stories of drink swilling immigrants, particularly targeting the Irish and their “notorious groggeries.” Outlawing alcohol, he predicted, would result in “better public buildings, better ways of living, in multiplied and enlarged industries, and in prosperous, thrifty, happy homes.”

After co-founding the Maine Temperance Society in 1827 at the age of 23, Dow became a five foot, two inch, firebrand speaker against the evils of liquor. His orations were filled with horror stories of drink swilling immigrants, particularly targeting the Irish and their “notorious groggeries.” Outlawing alcohol, he predicted, would result in “better public buildings, better ways of living, in multiplied and enlarged industries, and in prosperous, thrifty, happy homes.”

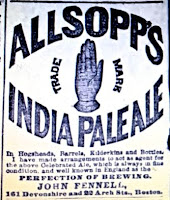

Increasingly Maine residents listened to him. An 1846 effort by the state legislature to promote liquor sales proved in ineffective. In 1851, however, Dow was elected mayor of Portland and with Maine Temperance Society members drafted a more stringent law, pushed legislators to pass it and the governor to sign. The law, earliest in the Nation, made Dow famous with prohibitionists throughout Northern States and he was widely in demand as a speaker. As mayor he was quick to crack down on drinking in Portland, directing raids against saloons and allowing the booze to flow in the gutters while the thirsty looked on. Elected again in 1855 by only a slim margin, Dow nevertheless pledged to double down on alcohol suppression.

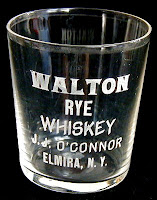

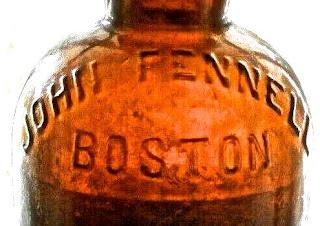

Here things get murky. Because whiskey was still part of the medical pharmacology, Maine law allowed towns to appoint one government agent, aided by a selection committee, as the sole legal entity to buy and distribute spirits intended for “non-beverage” use. Apparently not willing to give up personal authority over alcohol, Dow disregarded the law and in his own name bought a stash of booze valued then at $1,600 ($56,000 today). His purchase probably contained rum, whiskey and grain alcohol. Only when it arrived in Portland did he bother to inform his colleagues. Dow put the liquor under lock and key in City Hall in what came to be known as “The Rum Room.” He held the only key. It is not clear what he had in mind for the stocks. The situation suggests that he planned to supply it to doctors and druggists upon written requests he alone would approve. His antagonists, however, saw hypocrisy and wrongdoing.

Because the purchase had not been made under the letter of the law, the liquor theoretically became subject to seizure. Determined to embarrass Dow, his “wet” opponents drummed the matter into a major issue. They filed a complaint with the Portland police that the mayor’s purchase had been done illegally and now should be confiscated under the prohibitionary law. When police seemed slow to act, the protesters went to court. In Maine, any three citizens could ask a judge for a search warrant if they believed a crime had been committed. The protestors asked for and on June 2, 1855, were issued a warrant by a friendly local judge.

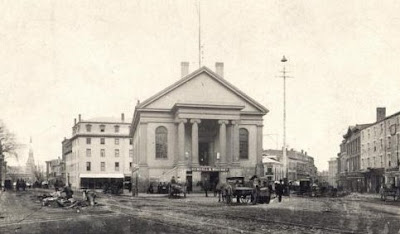

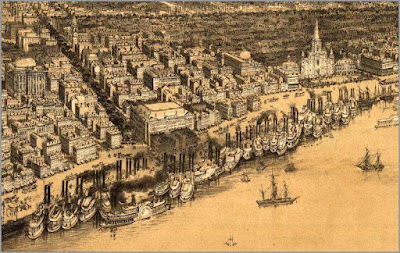

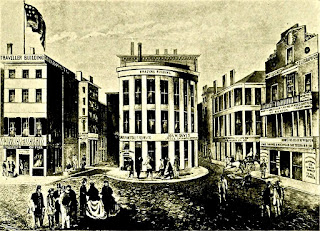

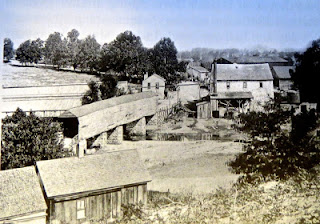

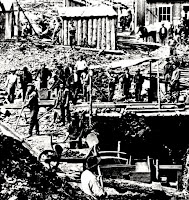

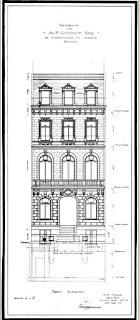

Brandishing the warrant, a small delegation went to City Hall, shown above, demanding entry so they could search the premises. By this time Dow had caught wind of their gambit and ordered police to bar the door. When it became evident that the police would not honor the warrant, the crowd grew to some 3,000 men. The mood became increasingly angry at the apparent duplicity of Maine’s leading temperance crusader having his own large supply of booze protected by the police. Shown here is one cartoonist’s (unfriendly) view of the protest.

Brandishing the warrant, a small delegation went to City Hall, shown above, demanding entry so they could search the premises. By this time Dow had caught wind of their gambit and ordered police to bar the door. When it became evident that the police would not honor the warrant, the crowd grew to some 3,000 men. The mood became increasingly angry at the apparent duplicity of Maine’s leading temperance crusader having his own large supply of booze protected by the police. Shown here is one cartoonist’s (unfriendly) view of the protest.

In an attempt to avoid violence Portland police officers locked themselves in the Rum Room and refused to disburse the crowd. An angry Mayor Dow then sent word to local militia companies to come quickly. Sensing impending disaster, one arriving sergeant suggested his men should load blanks. The diminutive Mayor Dow disagreed: “We know what we are about sir. We’ve consulted the law, sir.”

At ten o’clock that night one militia group of about twenty men formed up in front of City Hall. Now backed by armed troops, Mayor Dow personally ordered the crowd to disperse. They responded with a hail of trash and garbage. Dow ordered the troops to fire to keep the mob at bay. Their commander, a Captain Green, begged off, said his troops were insufficient, and asked permission to leave to recruit more men. A reluctant Dow assented.

It was a mistake. The sight of the militia marching off encouraged the crowd to become more aggressive. Rocks and bricks were thrown. The rioters discovered that the Rum Room had a door opening to the outside. John Robbins, a 22 year old sailor from nearby Deer Isle, said to have been on the eve of his wedding, broke a window, crawled inside and unlocked the door. The crowd moved forward. Just then the strengthened militia returned. At Dow’s command, they opened fire. Robbins was killed instantly. As the crowd dispersed in panic, the firing continued for twenty minutes. Seven protesters were wounded. Only because the militiamen were armed with antiquated muskets reputedly prevented the death toll from being higher. To “drys” it became known as the Portland Rum Riot. To “wets” it was the Portland Massacre.

In the days to follow Dow was charged with breaking the law he had helped pass, but was acquitted after a one day trial. The judge was a strong prohibitionist and a Dow supporter who ruled that the city — not Dow — owned the liquor. Considering himself exonerated, the mayor immediately issued a “Message on the Riot” in which he claimed John Robbins was an Irish immigrant who was wanted by the law. It was a lie. Witnesses under oath testified that Robbins had been born in America, had never been arrested, and was a “steady, honest man, remarkable for his good nature and peaceable disposition.” Nor was Robbins of Irish descent.

Historian Jack S. Blocker Jr. summed up the effects of the day’s events. The shootings, he says: “Irretrievably tarnished the prohibitionist dream of an orderly world of upwardly mobile abstainers…of Americans who were drawn to the vision of peace and prosperity that the enthusiastic prohibitionists such as Dow himself set before them.” Dow’s reputation in Maine also took a severe blow. Anti-prohibition media accused him of murder. His attempt to be elected to a third term failed. Opposition to the Maine law was strengthened as public opinion shifted and it was repealed the following year. Dow’s rush to use lethal force had undone his singular success.

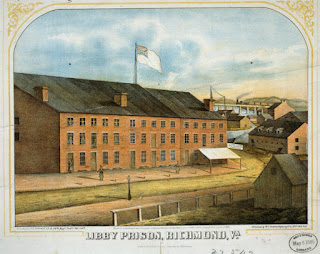

Elsewhere his standing among prohibitionists remained intact, sought as a speaker in the U.S. and England. Also ardently against slavery, Dow at the age of 57 in 1861 volunteered for service in the Union Army during the Civil War, was made a colonel, and promoted to brigadier general. Captured by rebels through a fluke, he spent eight months in a Confederate prison before being exchanged. After the war he returned to his anti-alcohol crusade. When the Prohibition Party was formed in 1880, Dow became its first candidate for president, receiving a paltry 10,305 votes.

Elsewhere his standing among prohibitionists remained intact, sought as a speaker in the U.S. and England. Also ardently against slavery, Dow at the age of 57 in 1861 volunteered for service in the Union Army during the Civil War, was made a colonel, and promoted to brigadier general. Captured by rebels through a fluke, he spent eight months in a Confederate prison before being exchanged. After the war he returned to his anti-alcohol crusade. When the Prohibition Party was formed in 1880, Dow became its first candidate for president, receiving a paltry 10,305 votes.

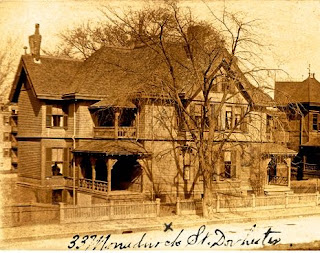

As he aged, Dow curtailed his speaking activities, residing in the family home shown above, with his daughter and married son. In October 1897, at age, 93, he died. His body lay in state in Portland’s Second Parish Church prior to burial in the city’s Evergreen Cemetery. The ardent prohibitionist had begun to write his memoirs but never lived to finish them. Too bad. Neal Dow, “Father of Prohibition,” might have revealed in them exactly what he had in mind when he bought all that riot-causing liquor.

As he aged, Dow curtailed his speaking activities, residing in the family home shown above, with his daughter and married son. In October 1897, at age, 93, he died. His body lay in state in Portland’s Second Parish Church prior to burial in the city’s Evergreen Cemetery. The ardent prohibitionist had begun to write his memoirs but never lived to finish them. Too bad. Neal Dow, “Father of Prohibition,” might have revealed in them exactly what he had in mind when he bought all that riot-causing liquor.

Note: Articles about Neal Dow and the Portland Rum Riot are numerous. They also vary on some important details. I have tried to select accounts that have more than one source. As an addendum to this story, I have added below a postcard issued by a local newspaper during National Prohibition of a 1920s “Rum Room” in Portland’s City Hall.