Thomas Sherley — Distiller with a Heart and a Hand

“When you give to the needy do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing.” — Mathew 6:3.

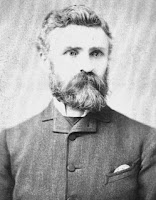

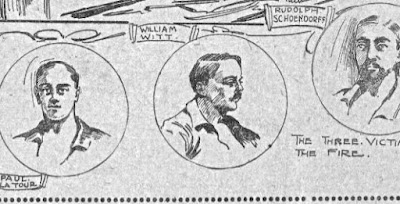

Although today Thomas H. Sherley, shown here, lacks the attention paid to other 19th Century Kentucky “bourbon barons.” his record of public service and most particularly his charitable endeavors eclipsed most if not all of them. At his death, the Louisville Courier Journal of November 30, 1898, in an extensive obituary related some of the philanthropy Sherley had performed during his lifetime.

Although today Thomas H. Sherley, shown here, lacks the attention paid to other 19th Century Kentucky “bourbon barons.” his record of public service and most particularly his charitable endeavors eclipsed most if not all of them. At his death, the Louisville Courier Journal of November 30, 1898, in an extensive obituary related some of the philanthropy Sherley had performed during his lifetime.

The newspaper recounted how Sherley had raised a fund to assist the victims of the Louisville Great Cyclone of 1890 that killed 76 people, injured some 200, and devastated much of the city’s downtown, inflicting the equivalent today of more than $86 million in damages. Sherley organized a fund for the victims of the calamity that aided hundreds. The Courier Journal recounted that after the money had been exhausted, a young woman victim repeatedly approached Sherley for help. He could not turn her away. She never learned that the amounts he gave her came from his own pocket and not from the fund.

The newspaper recounted how Sherley had raised a fund to assist the victims of the Louisville Great Cyclone of 1890 that killed 76 people, injured some 200, and devastated much of the city’s downtown, inflicting the equivalent today of more than $86 million in damages. Sherley organized a fund for the victims of the calamity that aided hundreds. The Courier Journal recounted that after the money had been exhausted, a young woman victim repeatedly approached Sherley for help. He could not turn her away. She never learned that the amounts he gave her came from his own pocket and not from the fund.

Serving six terms on the Louisville school board, at least one term as president, Sherley was passionate about providing education to those at the low end of the economic scale, including leading in the formation of night schools for workers. He was credited by the newspaper with fostering Black school students and spearheading building schools for them. He was credited with helping many Louisville young men and women enroll in business college, often paying their tuition, and helping them secure employment upon graduation.

A business associate told the reporter of an incident that draws on the Biblical quote that opens this post. Without Sherley’s knowledge the associate had begun to keep an account of the distiller’s charitable giving. When Sherley finally saw it, he inquired and was told, “That’s the charity account.” He threw it aside, quoted saying, “I don’t want to know what is given away. We don’t need the account.”

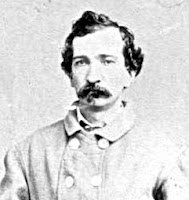

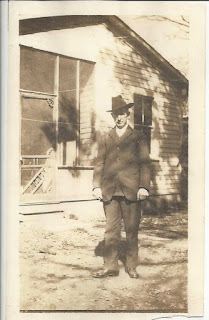

This successful Kentucky whiskey man was born in Louisville on New Year’s Day 1843, the son of Zachary and Susan Sherley. His father, shown here, was a riverboat pilot who had prospered to the point of owning a fleet of steamships. Zachary, originally from Virginia, was firmly on the side of the Union when the Civil War broke out in a state sharply divided over the conflict. In April 1862 he is credited with moving 25,000 troops and supplies from Louisville to Tennessee for the battle of Shiloh in support of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Later Zachary assisted Grant with ships during the battle for Fort Donelson. Although of eligible age as the war raged on, there is no evidence that Thomas Sherley ever served.

This successful Kentucky whiskey man was born in Louisville on New Year’s Day 1843, the son of Zachary and Susan Sherley. His father, shown here, was a riverboat pilot who had prospered to the point of owning a fleet of steamships. Zachary, originally from Virginia, was firmly on the side of the Union when the Civil War broke out in a state sharply divided over the conflict. In April 1862 he is credited with moving 25,000 troops and supplies from Louisville to Tennessee for the battle of Shiloh in support of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Later Zachary assisted Grant with ships during the battle for Fort Donelson. Although of eligible age as the war raged on, there is no evidence that Thomas Sherley ever served.

The young Sherley attended local schools, able because of his father’s wealth to graduate with a post-secondary degree in 1863. Shortly after, at the age of 21 he married Ella Swager, 20, the daughter of Capt. Joseph Swager, a steamboat captain and friend of his father. The 1870 federal census found the couple living in Louisville with three children, Eva Belle, Zach, Clara, and Ella’s 77-year old father. Sherley’s occupation given as “wholesale liquor,” He clearly was prospering. His household included three female servants — nurse, cook, and maid. By the 1880 census, the couple had added two more children, Swager and Minnie. Sherley was now listed as “distiller.”

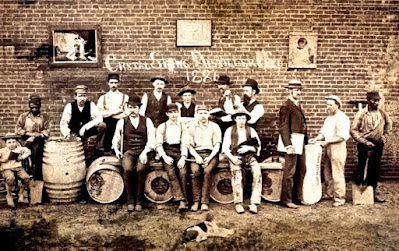

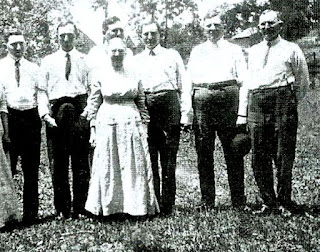

Sherley proved to be an energetic entrepreneur. With business partner E.L. Miles he ran two distilleries at New Hope, Kentucky, 55 miles south of Louisville. Built side by side, the first was called The New Hope Distilling Company (RD#101, 5th District) and founded by Miles’ father. It had a small mashing capacity of 20 bushels a day. As both a distiller and commission merchant, Sherley handled the output of the plant and about 1875 teamed with Miles to build the E. Miles Distillery (RD#146, 5th District) next door. This was a much larger plant, one originally processing 200 bushels daily. By 1885 the partners had expanded the capacity to 1,000 bushels. Sherley was also involved with the Crystal Springs Distillery (RD #3, 5th District) in Jefferson County with partner T. J. Batman. [See post on Batman, July 24, 2021.] A photo of that facility apparently shows Sherley (long black beard) among the workers.

Sherley proved to be an energetic entrepreneur. With business partner E.L. Miles he ran two distilleries at New Hope, Kentucky, 55 miles south of Louisville. Built side by side, the first was called The New Hope Distilling Company (RD#101, 5th District) and founded by Miles’ father. It had a small mashing capacity of 20 bushels a day. As both a distiller and commission merchant, Sherley handled the output of the plant and about 1875 teamed with Miles to build the E. Miles Distillery (RD#146, 5th District) next door. This was a much larger plant, one originally processing 200 bushels daily. By 1885 the partners had expanded the capacity to 1,000 bushels. Sherley was also involved with the Crystal Springs Distillery (RD #3, 5th District) in Jefferson County with partner T. J. Batman. [See post on Batman, July 24, 2021.] A photo of that facility apparently shows Sherley (long black beard) among the workers.

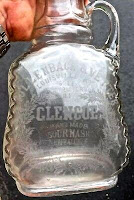

Among other enterprises, Sherley was a founding investor in Louisville’s Kentucky Public Elevator Co., shown left. He also co-owned the Southern Glass Works, a factory that manufactured a wide variety of medicinal glassware, fruit jars and flasks. Below is an example of a bottle with the glassworks signature mark.

Among other enterprises, Sherley was a founding investor in Louisville’s Kentucky Public Elevator Co., shown left. He also co-owned the Southern Glass Works, a factory that manufactured a wide variety of medicinal glassware, fruit jars and flasks. Below is an example of a bottle with the glassworks signature mark.

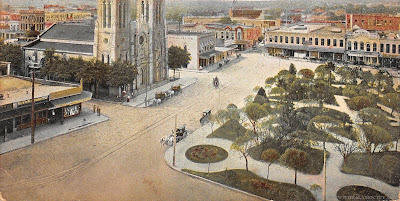

In addition to his enterprises and philanthropic work, Sherley also left his mark in the civic and political life of Louisville. Among his accomplishments Sherley was the first president of the Board of Parks Commissioners, serving for eight years. He served six terms as a member and president of the Louisville School Board, and twice was elected as a director of the Board of Trade. He was chairman of the citizens’ committee for Louisville’s hosting of a Grand Army of the Republic national convention.

In politics Sherley served from 1892 to 1896 as a representative to the Democratic National Committee from Kentucky, frequently called East to confer with Democratic leaders. He chaired the Kentucky delegation to the 1896 Democratic Convention in Chicago that nominated William Jennings Bryan and was considered the same year as a Democratic congressional candidate, but declined. Shown here, his son, Swager, later would be elected to a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In politics Sherley served from 1892 to 1896 as a representative to the Democratic National Committee from Kentucky, frequently called East to confer with Democratic leaders. He chaired the Kentucky delegation to the 1896 Democratic Convention in Chicago that nominated William Jennings Bryan and was considered the same year as a Democratic congressional candidate, but declined. Shown here, his son, Swager, later would be elected to a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

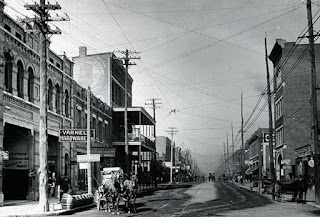

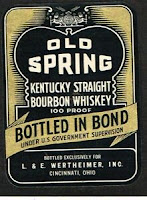

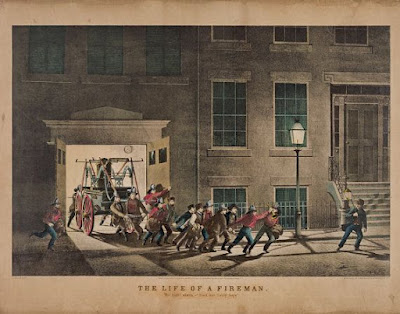

Perhaps the pinnacle of Sherley’s career as Kentucky distiller came in March 1891 when most of Kentucky’s leading distillers, the largest gathering ever of the state’s “bourbon barons,” gathered at Louisville’s Galt House hotel, shown left. Their purpose was to consider whether to organize a Kentucky Distillers’ Association with the purpose of promoting legislation helpful to the industry and, with an eye on the prohibitionary forces, “guarding the common interest against unjust legislations, state or national.” The man called upon to chair this august group was Thomas Sherley. Subsequently elected its president, he proved his value by being a skillful advocate for the Bottled-in-Bond bill, traveling frequently to Washington to testify before Congress and confer with political leaders.

Perhaps the pinnacle of Sherley’s career as Kentucky distiller came in March 1891 when most of Kentucky’s leading distillers, the largest gathering ever of the state’s “bourbon barons,” gathered at Louisville’s Galt House hotel, shown left. Their purpose was to consider whether to organize a Kentucky Distillers’ Association with the purpose of promoting legislation helpful to the industry and, with an eye on the prohibitionary forces, “guarding the common interest against unjust legislations, state or national.” The man called upon to chair this august group was Thomas Sherley. Subsequently elected its president, he proved his value by being a skillful advocate for the Bottled-in-Bond bill, traveling frequently to Washington to testify before Congress and confer with political leaders.

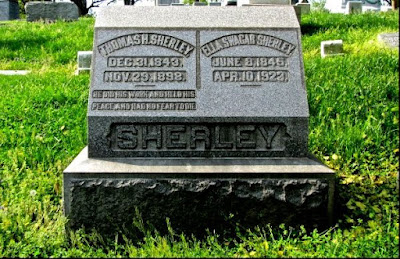

The many responsibilities Sherley carried on his shoulders might have crushed a lesser man years earlier. At age 55, he would not prove immune. In November 1898, according to the Courier Journal, the distiller began to feel ill. His doctor diagnosed him as suffering from indigestion and lung congestion but said the conditions were not serious. Sherley resumed his heavy schedule, dictating letters, meeting with associates in his business activities, and planning a national meeting of his Masonic order. On the morning of November 28, 1898, he arose from his bed to sit in a chair. He later was found there unconscious and died shortly thereafter. The verdict: Heart failure. His funeral, held at Louisville’s Episcopal Cathedral, and burial was a major event with large attendance and considerable ceremony. As many of Louisville’s distilling gentry, Sherley was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery, Section P, Lot 235, Grave 5. The inscription on his headstone reads: “He did his work and held his peace and had no fear to die.” Ella would join him in the grave 25 years later.

Of the many qualities that Thomas Sherley exhibited in his truly extraordinary life, I most admire his gift for giving, said to have practiced his philanthropy without distinction of “creed or color” and disdaining to keep track of his charity. This great hearted whiskey man had heeded the Biblical injunction. His right hand unconditionally was held out to the needy.

Notes: Although I had mentioned Thomas Sherley in my earlier post on Thomas Batman of Louisville, the distiller was brought fully to my attention by a recently published book by Bryan S. Bush entitled “Bluegrass Bourbon Barons,” American Palate, a Division of The History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2021. Author Bush covers the history of Kentucky and particularly Louisville-based whiskey-making through short biographies of the distillers. The obituary of Sherley in the Louisville Courier Journal provided a wealth of information, supplemented by other sources.