A Slab Seal Bottle Opens the Book on J. C. Marks

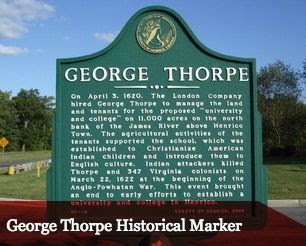

Marks’ shrewd approach toward “dry” forces was first manifested in the late 19th Century when Shelby County, some 30 miles down the road from Birmingham, required a license to sell liquor within its boundaries. Marks dispatched a traveling salesman named Newman into the jurisdiction. There Newman took an order for a gallon of whiskey costing $2.50 from B.L. Moore, who turned out to be shill for the prohibitionists. The authorities pounced on Newman, who protested that he was only an agent. The sale, he contended, had taken place in Birmingham when J. C. Marks, who had a license there, filled the order and sent the whiskey to Moore. The Supreme Court of Alabama agreed. Newman (and Marks) prevailed, continuing to sell liquor in Shelby County.

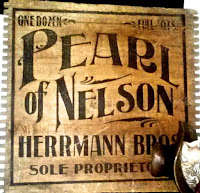

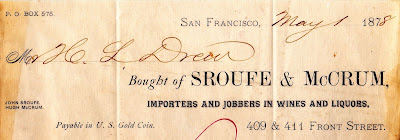

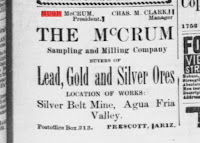

With a former local schoolmaster Adolph S. Loventhal, Marks in 1887 had open a liquor, wine and cigar business with offices, warehouse and workspace in a four story building at 2117 Second Avenue in Birmingham. These quarters allowed Marks to market his own brand of whiskey, blending it from barrels received by rail from Kentucky and elsewhere to achieve a desired taste, color and smoothness. His flagship label was “Three Red Barrels,” a name he trademarked in 1906.

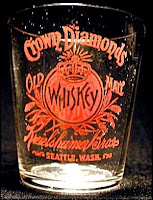

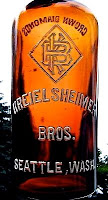

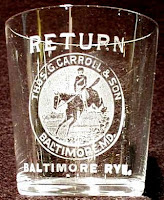

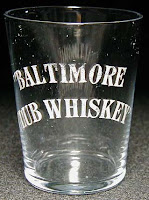

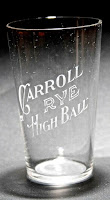

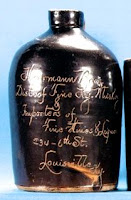

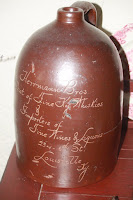

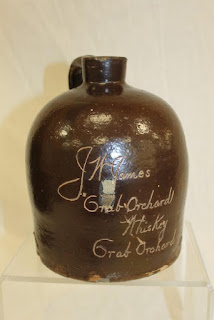

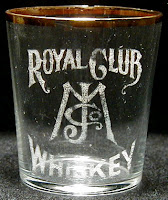

Like other whiskey wholesalers, Marks featured giveaway items to favored customers, both wholesale and retail. Below are two examples that have come to light. Below left is a crude mini jug with Marks’ name scratched in the Albany slip glaze. It is flanked by a much more elaborate mini. Note that this one advertises “3-Red-Barrels.”

In 1892 Adolph Loventhal, only 46, died, leaving behind his widow, Rebecca, (nee Sobel), and a sixteen year old son, Allison. Eleven years later Marks, a 43-year old bachelor, married Rebecca, who was five years older than he. Their union lasted 17 years until Marks’s death. No children are recorded from their union.

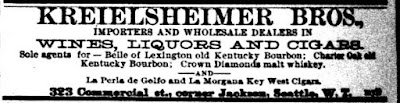

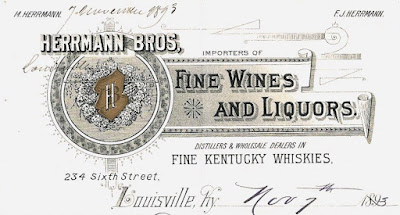

Although Marks could circumvent county license laws there was no way, or so it seemed, to get around the absolute statewide ban against the making and sales of alcoholic beverages imposed in Alabama in 1908. The whiskey wholesaler promptly moved his operation to a center of the whiskey industry, Louisville, Kentucky. This time, protected by the Interstate Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution with perfect legality he could ship his whiskey into any “dry” state or locality in America.

As he had found a way around the strictures of Shelby County, Marks had found a way legally to stay in Birmingham. Marks’ strategy was revealed in a 1917 advertisement that appeared in Birmingham newspapers. Its headline reads: “Buy for Christmas Before the Christmas Rush where Purity, Quality, Reliability for 25 Years has builded The Largest Wholesale Liquor Business in the South.” Reading down to the bottom, the J.C. Marks Liquor Company claimed to be operating from its “Same Old Stand” in Birmingham.

Now operating from “wet” Kentucky this whiskey man had determined that so long as the money transaction and shipping took place from Louisville, he could use his original Birmingham location to take and transmit orders. The payment went directly from customers to Marks in Louisville and the liquor was express mailed back to Birmingham. All this was perfectly legal. The state’s prohibitionists must have been furious.

Marks was not alone in such strategies, leading the Congress in 1913 to pass the Webb-Kenyon Act that removed the Constitutional protection for interstate sales. Because of court challenges, eventually reaching the U.S. Supreme Court, enforcement did not occur until several years later. By that time Marks now in his late 50s had closed out his liquor house and moved with Rebecca to Cleveland Heights, Ohio, to live among relatives. He died there at the age of 60, having seen the imposition of National Prohibition. Rebeca followed him to the grave a year later. Both lie in the Temple Cemetery of Nashville, Tennessee, in Section A, Lot 38, graves 1 and 2.

For 30 years via several strategies, Joseph Marks was able to circumvent the efforts of the prohibitionist to shut off the making and sale of liquor. In the end, however, those forces proved too strong to be overcome by any single individual and, indeed, for an entire industry.

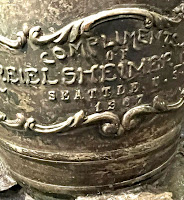

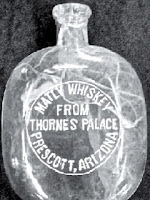

Note: Seeing the J.C. Mark slab seal bottle on the Internet, brought me to the David Jackson article, a record of the Shelby County case, and other sources of information on J.C. Marks. The picture of Mark’s “scratch” jug is through the courtesy of Bill Garland, the guru of Alabama whiskey ceramics.