The Sazerac Company is one of the two largest spirits companies in the United States with annual revenues of more than $1 billion, running some nine distilleries, employing an estimated 2,000 people and operating in at least 12 countries. The business owes its origins to a returned Confederate soldier who purchased a 19-year old New Orleans bar in 1869 and thereby founded a beverage behemoth. His name was Thomas Hughes Handy, shown here.

The Sazerac Company is one of the two largest spirits companies in the United States with annual revenues of more than $1 billion, running some nine distilleries, employing an estimated 2,000 people and operating in at least 12 countries. The business owes its origins to a returned Confederate soldier who purchased a 19-year old New Orleans bar in 1869 and thereby founded a beverage behemoth. His name was Thomas Hughes Handy, shown here.

Handy was born in 1839 in Somerset County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, from a family founded by ancestor Samuel Handy, who had arrived in Maryland from England as an indentured servant in colonial times, married Mary Sewell in 1679, and had 14 children. Among Samuel’s descendants was John Scarborough Handy who with wife Elizabeth moved his family to New Orleans in 1847, shown below, and died shortly thereafter, leaving Thomas, two brothers and a sister. The loss caused all the Handy sons to truncate their educations and go to work by their mid-teens. The 1860 census found the three boys working as clerks. Later Thomas was quoted saying that the happiest day of his life was when he had given his mother his first earnings.

By the early 1860s, Handy was working for a liquor importer named Sewell Taylor and learning the trade. When the Civil War erupted, however, he was quick to enlist in a Confederate unit known as the Crescent Light Artillery, commissioned a second lieutenant, and deployed to defend Fort St. Philip, a masonry redoubt located on the east bank of the Mississippi River and meant to protect New Orleans eighty miles upstream. Deemed critical to the Union cause, the Federal navy was deployed to take the fort, control the river and capture the city.

Standing against their bombardment of the fort was Captain T. H. Hutton, Lt. Handy and a company of raw troops that suffered from a lack of water, food, blankets, shelter, and medical attention while withstanding twelve days of relentless Union shelling, shown here in a magazine illustration. The siege of Fort St. Philip ended in a mutiny by the Confederate troops and an abject surrender. New Orleans quickly fell to the Yankees.

Standing against their bombardment of the fort was Captain T. H. Hutton, Lt. Handy and a company of raw troops that suffered from a lack of water, food, blankets, shelter, and medical attention while withstanding twelve days of relentless Union shelling, shown here in a magazine illustration. The siege of Fort St. Philip ended in a mutiny by the Confederate troops and an abject surrender. New Orleans quickly fell to the Yankees.

Captain Hutton, Handy and the others were captured. As an officer, Handy was sent east to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. He was lucky. Shown here, it was a relatively benign prison for Confederate officers, Southern sympathizing civil officials from Maryland, and Northern political prisoners. The commandant was known for his humane treatment of prisoners and the mortality rate was low. In any case, Handy was there for only a few weeks before being sent to back to the Confederacy in a prisoner exchange, common in the early stages of the war.

Freedom still eluded him, however, as Confederate military officials, rankled over the debacle at Fort St. Philip, arrested him for insubordination and mutiny. Put on trial in a court-martial, Handy appears to have used his characteristic eloquence to exonerate himself and rejoin the Crescent Artillery. There he found an opportunity to redeem his reputation.

His unit was deployed south of Vicksburg protecting Confederate supply lines on the Red River. When Union commanders sent the gunship, SS Indianola, to disrupt river traffic, Handy, aboard an armed Confederate steamship, was given command of the troops. As author John C. Tramazzo says: “The valiant and perhaps reckless, Lt. Thomas Handy attacked with vigor.” The result was total victory with the Indianola disabled, its cargo plundered, and its crew captured.

His unit was deployed south of Vicksburg protecting Confederate supply lines on the Red River. When Union commanders sent the gunship, SS Indianola, to disrupt river traffic, Handy, aboard an armed Confederate steamship, was given command of the troops. As author John C. Tramazzo says: “The valiant and perhaps reckless, Lt. Thomas Handy attacked with vigor.” The result was total victory with the Indianola disabled, its cargo plundered, and its crew captured.

Handy went on from there for other victories against Union ships on the Red River. Captured a second time and released to a hospital in Shreveport, Louisiana, for treatment of his wounds and a broken leg, Handy resigned his commission, When the Confederates surrendered he returned to New Orleans.

Now afflicted with a permanent limp, Handy returned home a hero, hailed as one who “had done his full duty.” Drawing on his earlier experience in the whiskey trade he secured employment as the bookkeeper at a high class New Orleans saloon in the French Quarter called the Sazerac House. The setting is shown below. Saving his money, when the owner in bad health decided to sell out in 1871, Handy bought the business and kept the name.

This suggests a brief discussion of “Sazerac.” It is a cocktail initially made with a French brandy called “Sazerac de Forge et Fils.” The name tracks back to

This suggests a brief discussion of “Sazerac.” It is a cocktail initially made with a French brandy called “Sazerac de Forge et Fils.” The name tracks back to

France and the 1630s when the Sazerac family established vineyards and a distillery in the Cognac region. The current company is thoroughly American, with headquarters in Louisville, Kentucky, and owes its origins to Handy. Shown here is an 1875 ad he placed in which he claimed to be the New Orleans agent for Sazerac’s “justly celebrated” brandies.

During this period Handy also had a personal life. The 1870 census found him at 32 years old the head of an unusual household. A newlywed, his bride was Josephine “Josie” Campbell, a Mississippi-born young woman 11 years his junior. Living with them was Handy’s mother, Elizabeth; his younger brother, Frederick; Sally Mack, a relative,and her two minor children. Also in residence was James Quirk, a black servant, and Quirk’s aged mother. By the 1880 census, Thomas and Josie had three children, ages nine, four and four months. Handy’s mother and brother were still living with them but no other relatives or servants. His postwar years also found Handy taking responsibilities in New Orleans civic life. He served on the school board and as a livestock inspector. When a new Ninth Ward was created in 1876 he was elected to the post of “civic sheriff.” In that role he is credited with securing employment for as many as 5,000 confederate veterans.

By that time Handy’s roller coaster financial ride had begun in New Orleans. The same aggressive risk-taking that had characterized his storied military service was exhibited in his business dealings. With his saloon and liquor business generating considerable wealth, Handy launched himself as a local entrepreneur, creating Handy’s Canal Street, City Park & Lakeshore Railroad Company. This glorified streetcar linked Basin Street to the Spanish Fort Amusement Park on Lake Ponchartrain, shown below.

In 1878 the cost of construction and maintenance forced him into bankruptcy. The Sazerac website describes what happened next: “After Handy loses his money in bad railroad investments, he is forced to dissolve Thos. H. Handy Co….Shortly after Vincent Micas buys out Thomas Handy becoming the owner of the Sazerac House….” Micas also became the agent for Sazerac brandy, and involved himself in a bitter dispute with Handy.

Four years later the tables turned. In March 1882 Micas suffered financial problems, lost his lease on the Sazerac House, and saw his building demolished. His fortunes revived, Handy — now known as “Colonel Handy” — rebuilt and reopened the Sazarac House at its original location. The Times-Picayune reported: “The structure has been put up by Col. Handy who has planned it for a grand resort, to be unsurpassed for comfort, elegance and convenience.” The article enthused over the carved walnut bar, the carved paneling and fancy fixtures, ending: “Good fare and good liquors will be the watchword of the “new Sazarac.” The building as it looks today is shown below.

Four years later the tables turned. In March 1882 Micas suffered financial problems, lost his lease on the Sazerac House, and saw his building demolished. His fortunes revived, Handy — now known as “Colonel Handy” — rebuilt and reopened the Sazarac House at its original location. The Times-Picayune reported: “The structure has been put up by Col. Handy who has planned it for a grand resort, to be unsurpassed for comfort, elegance and convenience.” The article enthused over the carved walnut bar, the carved paneling and fancy fixtures, ending: “Good fare and good liquors will be the watchword of the “new Sazarac.” The building as it looks today is shown below.

With his new saloon becoming a fashionable gathering place for New Orleans elites and the Sazarac franchise now firmly back in hand, Handy again was on a firm track. Tradition has it that he subsequently substituted rye whiskey for the original brandy in the Sazarac cocktail without his patrons objecting His prosperity restored, Handy was able to buy a summer home on Mississippi’s Long Beach resort area. At the relatively young age of 54, Handy died there in 1893.

With his new saloon becoming a fashionable gathering place for New Orleans elites and the Sazarac franchise now firmly back in hand, Handy again was on a firm track. Tradition has it that he subsequently substituted rye whiskey for the original brandy in the Sazarac cocktail without his patrons objecting His prosperity restored, Handy was able to buy a summer home on Mississippi’s Long Beach resort area. At the relatively young age of 54, Handy died there in 1893.

Handy’s funeral was a major event, with delegations present from the American Legion of Honor, Knights of Honor and the Army of Tennessee. Among the tributes that poured in he was called: “A true man — true to himself and to mankind. He had been a friend to those in want….and his willing hand always assisted the good cause when needed.” Handy was buried in New Orleans’ Metairie Cemetery, his crypt shown here. Josie would join him there 30 years later.

Handy’s funeral was a major event, with delegations present from the American Legion of Honor, Knights of Honor and the Army of Tennessee. Among the tributes that poured in he was called: “A true man — true to himself and to mankind. He had been a friend to those in want….and his willing hand always assisted the good cause when needed.” Handy was buried in New Orleans’ Metairie Cemetery, his crypt shown here. Josie would join him there 30 years later.

The company Handy founded was perpetuated and later formally chartered as the Sazerac Company. Since then under the ownership of William Goldring, the company has come to operate Buffalo Trace, Barton, A. Smith Bowman, Medley, Fleischmann, Mr. Boston, Glenmore and other distilleries. The organization continues to hail Thomas Handy for his hard work and tenacity as the source of its success. Shown here is a Sazerac whiskey that commemorates the founder.

The company Handy founded was perpetuated and later formally chartered as the Sazerac Company. Since then under the ownership of William Goldring, the company has come to operate Buffalo Trace, Barton, A. Smith Bowman, Medley, Fleischmann, Mr. Boston, Glenmore and other distilleries. The organization continues to hail Thomas Handy for his hard work and tenacity as the source of its success. Shown here is a Sazerac whiskey that commemorates the founder.

Notes: Among the important sources for this post were John Tremazzo’s interesting book, “Bourbon and Bullets: True Stories of Whiskey, War, and Military Service” (2018), the Sazerac Company website history, and genealogical sites.

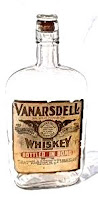

Moore dubbed the location “Vanarsdell” and called his premier bourbon the same name. He advertised the brand extensively. Shown here is an apparently unembossed clear quart bottle of “Vanarsdell Hand Made Sour mash” whose colorful label alone apparently made it worth $2,100 at auction recently. Below are two views of a Vanarsdell flask, also apparently unembossed. Another Moore brand was “Stone Wall Whiskey.” He also produced whiskeys sold by Charles Rebstock, a leading liquor wholesaler of St. Louis. [See my post on Rebstock at September 6, 2011.]

Moore dubbed the location “Vanarsdell” and called his premier bourbon the same name. He advertised the brand extensively. Shown here is an apparently unembossed clear quart bottle of “Vanarsdell Hand Made Sour mash” whose colorful label alone apparently made it worth $2,100 at auction recently. Below are two views of a Vanarsdell flask, also apparently unembossed. Another Moore brand was “Stone Wall Whiskey.” He also produced whiskeys sold by Charles Rebstock, a leading liquor wholesaler of St. Louis. [See my post on Rebstock at September 6, 2011.]