While a student at a Baptist college in his native Kentucky, John Gaines Roach became a Baptist convert through the rite of immersion. He is said to have “remained a devout and active member for the remainder of his life.” Roach’s religious affiliation, however, failed to deter him from owning and operating three whiskey-making distilleries at the same time or from building another when one burned.

While a student at a Baptist college in his native Kentucky, John Gaines Roach became a Baptist convert through the rite of immersion. He is said to have “remained a devout and active member for the remainder of his life.” Roach’s religious affiliation, however, failed to deter him from owning and operating three whiskey-making distilleries at the same time or from building another when one burned.

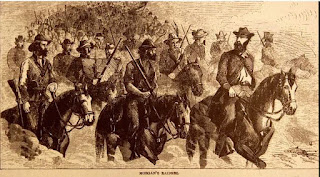

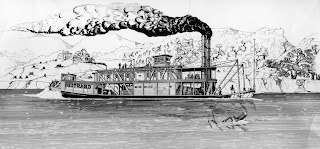

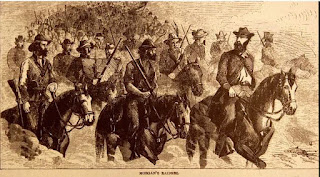

John was born in March 1845 in Campbellsville, Kentucky, the son of Martha P. White and J. J. Roach, a relatively wealthy farmer originally from Virginia. Although Kentucky was a border state that was controlled largely by Union forces, Roach left college in 1861 to join the elite Confederate cavalry of Kentuckian Gen. John Hunt Morgan. Participating in Morgan’s raids into the North, Roach helped capture two Ohio River steamers at Brandenburg, Kentucky, that allowed Morgan’s men to cross into Indiana, Ohio and ultimately West Virginia.

In July 1863, Roach was captured along with the bulk of Morgan’s men near Bluffington Island, West Virginia. Imprisoned initially at Columbus, Ohio, he was sent to the Union prison near Chicago. Called Camp Douglas, right, the facility was notorious for the high death rate among prisoners. Roach survived 18 months there and was released only after the surrender at Appomattox. He returned to Kentucky to find the Roach family fortunes in tatters and five of his seven cousins who had fought for the South among the slain.

In July 1863, Roach was captured along with the bulk of Morgan’s men near Bluffington Island, West Virginia. Imprisoned initially at Columbus, Ohio, he was sent to the Union prison near Chicago. Called Camp Douglas, right, the facility was notorious for the high death rate among prisoners. Roach survived 18 months there and was released only after the surrender at Appomattox. He returned to Kentucky to find the Roach family fortunes in tatters and five of his seven cousins who had fought for the South among the slain.

For the next four years Roach was occupied in coal mining and shipping operations in south central Kentucky. Ambitious and apparently finding this employment unrewarding, he moved to Louisville. That city had escaped damage during the war and its population was booming, increasing almost 50% from 1860 t0 1870. About a third were Roach’s fellow Baptists. Roach would have noted that population as well as Louisville’s increasing importance as a center of America’s distilling industry.

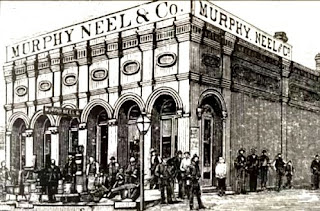

In 1869, with assistance from his father, Roach partnered with J.J. Grove, an established Louisville businessman, to start a liquor house called Grove, Roach & Company, located at 74-76 Sixth Street between Main and Market. In 1874, again with help from his father, he bought out Grove and changed the name of the business to John G. Roach & Company.

In the meantime, John was having a personal life. At the age of 25, he married Sally Neill, 18, the daughter of Mathew and Eliza Neill of Louisville. Her father was a prominent local industrialist. The couple would have two sons, Neill and Ethric. Sally like her husband was a Baptist and something of a scriptural expert. For more than 25 years she conducted Bible instruction for Sunday school teachers and contributed articles to religious publications, including the Baptist Expositor, a national doctrinal publication. Her view of her husband’s role in the Louisville liquor trade are unknown. She married him, however, when he was fully engaged in selling whiskey and it seems not to have troubled their relationship.

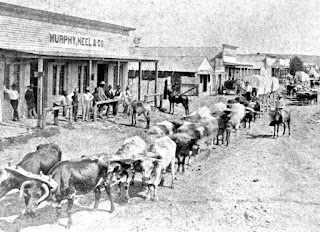

After five years of operating his liquor house, a restless John Roach sold the business and began to build and operate distilleries. The first was in Uniontown, Kentucky, 150 miles southwest of Louisville, described as “one of the best arranged and equipped distilleries in the United States.” Named the Rich Grain Distillery after the brand produced there, this facility, shown below, featured a two story still house with a capacity of mashing 1,000 bushels of grain a day, a three story elevator , and two warehouses with a capacity of 31,000 barrels. A newspaper reporter visiting the site extolled the offices, the malt-house and even the cattle pens. Rich Grain Whiskey, he claimed was sold “…From New York to San Francisco and Chicago to New Orleans.”

After five years of operating his liquor house, a restless John Roach sold the business and began to build and operate distilleries. The first was in Uniontown, Kentucky, 150 miles southwest of Louisville, described as “one of the best arranged and equipped distilleries in the United States.” Named the Rich Grain Distillery after the brand produced there, this facility, shown below, featured a two story still house with a capacity of mashing 1,000 bushels of grain a day, a three story elevator , and two warehouses with a capacity of 31,000 barrels. A newspaper reporter visiting the site extolled the offices, the malt-house and even the cattle pens. Rich Grain Whiskey, he claimed was sold “…From New York to San Francisco and Chicago to New Orleans.”

Roach’s second plant was the Old Log Cabin Distillery, again named for the proprietary brand of whiskey produced there. Located on Louisville’s waterfront, this facility included a three story still house with the capacity of mashing 600 bushels a day, two bonded warehouse that held 20,000 barrels, offices and a residence for the manager. The warehouses drew particular praise from an observer: “Here are to be seen two of the finest and bonded warehouses to be found in the state…supplied with all modern improvements in construction, patent ricks…forming a well-ventilated pyramid of barrels….It is one of the dryest and best ventilated warehouses in the district.”

The Bel Air Distillery subsequently was built by Roach on the outskirts of Louisville. It boasted a three story still house with a capacity of 600 bushels a day, an extensive warehouse that held 17,000 barrels, and a house for the manager. Said one report: “The distillery is adapted to its uses, having the engines and boilers on the ground and separate from the distillery proper.

The Bel Air Distillery subsequently was built by Roach on the outskirts of Louisville. It boasted a three story still house with a capacity of 600 bushels a day, an extensive warehouse that held 17,000 barrels, and a house for the manager. Said one report: “The distillery is adapted to its uses, having the engines and boilers on the ground and separate from the distillery proper.

In 1892 after the Rich Grain Distillery burned, Roach apparently decided that rhe long trek to Uniontown was too far and instead of rebuilding there, he constructed his fourth plant in Louisville. Known as the John G. Roach & Co. Distillery, this facility was located at 30th and Garland Streets. Insurance underwriter records for 1896 indicate that the distillery was of brick and iron-clad construction, with a brick boiler-house. The property included a separate mill building and cattle sheds, the later located 115 feet north of the still. Two warehouses were on the property. In 1893, the Louisville Courier Journal observed: “A large distiller from the interior of the State who recently went through this house, pronounced it by far the most perfect distillery he had ever seen, and the only one in existence that a man could operate, if he so desired, in a dress suit.”

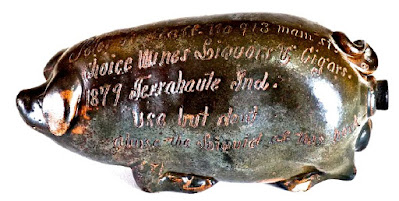

Among other whiskey brands that Roach featured from his distilleries was“Kentucky’s Sugar Corn,” and “Suwanee Pure Rye. He often bottled these in clear glass flasks, embossed with his name, city and legend: “Pure Kentucky Whiskies.” As shown below, Roach also was providing all the whiskey for the grocery and liquor business of Domenico Canale in Memphis. [See my post on Canale, Nov. 26, 2011.]

With frequent enthusiastic accolades as the owner/operator of major distilleries, Roach found himself celebrated among Kentucky’s “Whiskey Barons.” Meanwhile, however, Baptist leadership in Kentucky and elsewhere was taking an increasingly hard line against alcohol, ignoring the fact that Elijah Craig, a Baptist minister, had been among the earliest Kentucky distillers and credited by some as the creator of bourbon [See post Nov. 30, 2021]. In 1896 the Southern Baptist Convention leadership voted in favor of absolute prohibition of alcohol. They further declared that those Baptists selling or drinking spirits, wine or beer should be excommunicated from their congregations. All across southern and border states distillers, liquor dealers and saloon keepers were banned from Baptist worship.

How this interdiction was received by John Roach or his wife Sally has gone unrecorded. Nor is there any evidence of formal church action being taken against Roach. By 1900, however, the highly successful Kentucky distiller was selling off his properties. At least two of them went to the “Whiskey Trust.” They included the Louisville distillery bearing Roach’s name. Julius Kessler, the guiding force of the cartel, is recorded operating the facility from about 1903 until the coming of National Prohibition in 1920. Although Roach had not rebuilt the Rich Grain Distillery in Uniontown its warehouses remained. In 1892, he also sold that property to the Trust. Trust executives rebuilt the distillery and operated it under the name Mutual Distilling Co., and later as the Union County Distilling Co. The plant closed with Prohibition and was abandoned.

|

| Union National Bank Note |

At the time of his sell-off, Roach was still only 55. With the proceed of the sales he rapidly became an important figure in Louisville’s banking sector as a stockholder and director in the Union National Bank, the Bank of Commerce and the Louisville Insurance Company. He also was active in the local Democratic Party, serving as chairman from 1880 to 1892. There Roach’s affiliation with alcohol was no bar. So popular was he that a campaign was mounted in 1882 to draft him to run for mayor. He politely declined. Later, however, he accepted an appointment as commissioner for the county’s Central Insane Asylum. He was a delegate to the national Democratic Convention of 1884 as a supporter of Grover Cleveland, who was running in a field of eight. Cleveland won the nomination and ultimately the Presidency.

As they aged and with their sons grown the Roaches moved to a luxury apartment building called “The Parsons” on Bonnycastle Road. There at the age of 62 Roach died in December 1907. The cause given was “apoplexy and paralysis,” indicating the effects of a stroke. Indicating some Baptist ill-feeling toward the distiller, Roach was not buried from a church. His services, described as “simple,” were held in the family apartment by Rev. George Eager of the Southern Baptist Seminary. By contrast, when Sally died in 1938, her funeral was conducted at the Beechwood Baptist Church with relatives and friends in attendance. The couple are buried together in Cave Hill Cemetery where many whiskey “royalty” are interred.

Roach’s career as a distiller while being a devout Baptist with a wife active in church work indicates toleration or at least ambivalence among the denomination’s adherents during the late 19th Century. As “dry” forces increased their strength and vehemence against strong drink, however, leaders in the Baptist and other Protestant denominations harden their positions. I believe John Roach was forced to make a choice, and whatever his personal beliefs about alcohol, sold off his highly successful distilleries for religious reasons.

Note: More than usual in these posts newspaper articles involving Roach were crucial in weaving together this story of a Baptist whiskey man. The Louisville Courier Journal proved a rich source of information, apparently finding Roach and his distilleries worthy of considerable attention. Bryan Bush in his 2021 book “Bluegrass Bourbon Barons” provides a succinct biography of Roach. The publisher is American Palate, a division of the History Press, Charleston SC.