Hawaii’s Macfarlanes Flourished the Royal Way

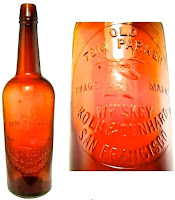

At a pivotal time in Hawaiian history, four brothers named Macfarlane used their liquor company as a springboard to wealth and influence with the native Hawaiian royalty. Their support for the “status quo” could not stem the tide of change, however, that would make the islands an American territory. A red amber bottle of their whiskey serves as to remind us of their lives and contributions.

At a pivotal time in Hawaiian history, four brothers named Macfarlane used their liquor company as a springboard to wealth and influence with the native Hawaiian royalty. Their support for the “status quo” could not stem the tide of change, however, that would make the islands an American territory. A red amber bottle of their whiskey serves as to remind us of their lives and contributions.

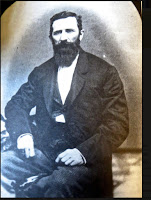

The Macfarlane brothers were sons of Henry Richard (Scottish) and Eliza (English) Macfarlane, a couple who met in and married in New Zealand before becoming early settlers of Hawaii, arriving in the islands in 1846. All but one of their children were born there. George W. Macfarlane, shown here, would launch the family into the liquor trade in 1877 by joining a partnership with W. L. Green, Hawaiian Minister of Finance, to create the firm of Green, MacFarlane & Co. Two years later George bought out Green and with his brother Henry R. Macfarlane started the firm of G.W. Macfarlane & Co. Although advertised as “shipping, commission and general wholesale merchants,” the principal product was liquor.

The Macfarlane brothers were sons of Henry Richard (Scottish) and Eliza (English) Macfarlane, a couple who met in and married in New Zealand before becoming early settlers of Hawaii, arriving in the islands in 1846. All but one of their children were born there. George W. Macfarlane, shown here, would launch the family into the liquor trade in 1877 by joining a partnership with W. L. Green, Hawaiian Minister of Finance, to create the firm of Green, MacFarlane & Co. Two years later George bought out Green and with his brother Henry R. Macfarlane started the firm of G.W. Macfarlane & Co. Although advertised as “shipping, commission and general wholesale merchants,” the principal product was liquor.

By 1892, George had moved on, becoming the manager of the original Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu. This early luxury hotel on Oahu, below, became a favorite “watering hole” for native Hawaiian royalty, including the heir apparent to the monarchy, Prince Kalakaua. A man with a taste for strong drink, the prince was well accommodated at Macfarlane’s hotel. When he became king, Kalakaua appointed George to his personal staff as a colonel, left, and subsequently as a privy councilor, member of the House of Nobles, and ultimately king’s chamberlain.

As chamberlain, George was responsible representing the king to the national cabinet and for floating bonds for Hawaiian projects on the London exchange amounting to millions. The bonds advanced government needs, sugar interests and the Hawaiian Street Railroad Company. In 1899, he organized the first American Bank of Hawaii with help from British and American financing. When King Kalakaua made a ‘round the world’ trip, George Macfarlane was close by his side, as shown here in a photograph.

As chamberlain, George was responsible representing the king to the national cabinet and for floating bonds for Hawaiian projects on the London exchange amounting to millions. The bonds advanced government needs, sugar interests and the Hawaiian Street Railroad Company. In 1899, he organized the first American Bank of Hawaii with help from British and American financing. When King Kalakaua made a ‘round the world’ trip, George Macfarlane was close by his side, as shown here in a photograph.

Meanwhile Henry Macfarlane was running the family business, now strictly involved with alcohol-related sales and called Macfarlane & Company. Henry appears to be the family member who was responsible for the amber whiskeys with the Macfarlane logo on the front. As shown below they came in varying shades of amber.

By 1896, Henry had been joined by younger brothers Clarence W. Macfarlane and Edward C. Macfarlane. Edward was listed as vice president; Clarence as a salesman and an agent for “Dr. Pottie’s Horse Medicine.” After five years with Macfarlane & Co. Clarence moved on from liquor sales and horse remedies to running an electric light company. He continued to be involved in family businesses that had evolved into saloons and hotels, including the Seaside Hotel that for a time Clarence managed.

Although recognized as a businessman, Clarence, shown here, became famous in Hawaii as a sportsman, organizing the first trans-Pacific yacht race. In 1906 he took his yacht, “La Paloma” to the Pacific Coast, arriving in San Francisco a few days after the earthquake and fire. The trip to the coast was made in 28 days, while the return voyage, at racing speed, was accomplished in 14 days. Today it is among the oldest of the world’s classic ocean races. Clarence also has been credited a the first white man to master the sports of surfboarding and outrigger canoeing. He is memorialized in the Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame.

Although recognized as a businessman, Clarence, shown here, became famous in Hawaii as a sportsman, organizing the first trans-Pacific yacht race. In 1906 he took his yacht, “La Paloma” to the Pacific Coast, arriving in San Francisco a few days after the earthquake and fire. The trip to the coast was made in 28 days, while the return voyage, at racing speed, was accomplished in 14 days. Today it is among the oldest of the world’s classic ocean races. Clarence also has been credited a the first white man to master the sports of surfboarding and outrigger canoeing. He is memorialized in the Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame.

King Kalakaua, who was an alcoholic, became very ill on an 1891 trip to the United States. George Macfarlane was with him in San Francisco’s Palace Hotel and is said to have sat at his bedside grasping the monarch’s hand as he died. The new queen Liliuokalani, a sister of Kalakaua, removed Macfarlane as chamberlain and appointed another to the post. But the Macfarlanes were not left out.

.jpg) In the legislative election of 1890, Edward Macfarlane ran and was successfully elected to the House of Nobles, the upper house of the Legislature of the Kingdom of Hawaii, for a four-year term. He sat in the legislative assembly of 1890 during the reign of King Kalākaua and during the 1892–93 session under Queen Liliʻuokalani. On September 12, 1892, Edward, shown left, became the head of the so-called “Macfarlane Cabinet.” Considered a trusted advisor by the queen, he was appointed Minister of Finance and formed his own cabinet. After serving a mere five weeks, on October 17 he and his colleagues were voted out by the legislature for lack of confidence. The queen, however, continued to consider Edward a trusted advisor.

In the legislative election of 1890, Edward Macfarlane ran and was successfully elected to the House of Nobles, the upper house of the Legislature of the Kingdom of Hawaii, for a four-year term. He sat in the legislative assembly of 1890 during the reign of King Kalākaua and during the 1892–93 session under Queen Liliʻuokalani. On September 12, 1892, Edward, shown left, became the head of the so-called “Macfarlane Cabinet.” Considered a trusted advisor by the queen, he was appointed Minister of Finance and formed his own cabinet. After serving a mere five weeks, on October 17 he and his colleagues were voted out by the legislature for lack of confidence. The queen, however, continued to consider Edward a trusted advisor.

Queen Lili’uokalani sought to restore power to the monarchy by abrogating the 1887 Constitution and adopting a new one. Her proposed 1893 Constitution would have increased native Hawaiian suffrage by reducing some property requirements and eliminated voting privileges extended to European and American residents. The queen’s initiative seems to have been broadly supported by the Hawaiian population, but triggered a reaction among powerful U.S. elements that led to her ousting and an American pineapple millionaire being named governor.

Queen Lili’uokalani sought to restore power to the monarchy by abrogating the 1887 Constitution and adopting a new one. Her proposed 1893 Constitution would have increased native Hawaiian suffrage by reducing some property requirements and eliminated voting privileges extended to European and American residents. The queen’s initiative seems to have been broadly supported by the Hawaiian population, but triggered a reaction among powerful U.S. elements that led to her ousting and an American pineapple millionaire being named governor.

In this virtually bloodless “coup d’tat,” the Macfarlanes, true to their dedication to the Hawaiian royal family, stood with the queen. In the end their influence mattered little and it is to be wondered how vociferous they were in her defense given their many business and financial interests in Hawaii. In addition to their liquor and hotel enterprises on Oahu the Macfarlanes were involved in sugar plantations on Maui, gas and electric utilities, and imports of machinery and fire equipment.

The Macfarlane’s support for the queen apparently was not a bar to their further advancement in Hawaii. Clarence became active in the Democratic Party. As a result, in 1920 he was appointed by the Wilson Administration as chairman of the Hawaiian Civil Service Commission. George continued to prosper in business. Henry operated Macfarlane & Co. until closed in 1918 by a decree of Woodrow Wilson related to World War I needs that banned liquor in Hawaii. He went on to be Danish Consul for the islands.

The Macfarlane’s support for the queen apparently was not a bar to their further advancement in Hawaii. Clarence became active in the Democratic Party. As a result, in 1920 he was appointed by the Wilson Administration as chairman of the Hawaiian Civil Service Commission. George continued to prosper in business. Henry operated Macfarlane & Co. until closed in 1918 by a decree of Woodrow Wilson related to World War I needs that banned liquor in Hawaii. He went on to be Danish Consul for the islands.

Edward’s future was less fortunate. For many years known as one of Hawaii’s wealthiest bachelors, he was 49 years old when he met Florence Ballinger, 22, a Chicago native while she was on an extended stay in Honolulu. They fell in love and were married in San Francisco in February 1902. The couple then set out for a honeymoon in Europe but had only reached Chicago before Edward became very ill, diagnosed as “pleuro-pneumonia,” and died. His body was returned to Hawaii for burial. A newspaper report commented: “Mrs. Macfarlane goes back to a home crowded with wedding presents which have not even been acknowledged.”

The four Macfarlane brothers are remembered today for the important roles they played in the history of Hawaii. Their success as liquor merchants clearly was an essential factor in their rise to prominence in both business and politics. Their links to alcohol, however, also helped bind them to an “ancien regime” whose days of ruling on the islands were numbered.

The four Macfarlane brothers are remembered today for the important roles they played in the history of Hawaii. Their success as liquor merchants clearly was an essential factor in their rise to prominence in both business and politics. Their links to alcohol, however, also helped bind them to an “ancien regime” whose days of ruling on the islands were numbered.

Note: I was drawn to the story of the Macfarlane “whiskey men” of Hawaii by seeing an embossed bottle with their company logo. Research soon disclosed that three of the four brothers merited their own entry, with photos, in Wikipedia. Those biographies provided essential information. Only Henry, who ran the liquor house, is absent a picture, an omission I am hopeful some alert reader will remedy.

.jpg-%20R.jpg)