Joseph John (“Joe”) Murphy, who spent more than a quarter century as its proprietor, boasted that his Ruby Saloon in Palestine, northeast Texas, was: “One of the oldest and best conducted Liquor Establishments” in the Lone Star State. Even so, Murphy would have to admit that as the site of dismantling Santa Anna’s knee buckle and a deadly shootout triggered by Palestine’s telephone service, sometimes the West could still be wild at the Ruby Saloon.

|

| Palestine, Texas 1880s |

Murphy was born in New Orleans in 1863, in the midst of the Civil War when Union troops ran the city. His father, John C., an immigrant from Ireland, died when the boy was only four. He and a sister, Mary Ellen, were raised by a single mother, Ellen Mary McGrath. At some point the family moved to Paris, Texas. In the late 1880s Murphy relocated 140 miles south to Palestine, a relatively small Texas city and the seat of Anderson County. There he founded the “The Ruby” saloon about 1888.

Shown above is Spring Street, the principal avenue of Palestine. Murphy’s establishment was near the center of the town’s business district and adjacent to Palestine’s major hostelry, the Lindell Hotel. This made for lively trade not just from locals but also visitors to town. Murphy believed in the power of advertising and his trade cards left no doubt that “The Dear Old Dollar” was welcome at The Ruby to buy “whiskies, wines and alcohol.” He saluted the coin in verse:

Shown above is Spring Street, the principal avenue of Palestine. Murphy’s establishment was near the center of the town’s business district and adjacent to Palestine’s major hostelry, the Lindell Hotel. This made for lively trade not just from locals but also visitors to town. Murphy believed in the power of advertising and his trade cards left no doubt that “The Dear Old Dollar” was welcome at The Ruby to buy “whiskies, wines and alcohol.” He saluted the coin in verse:

How dear to our hearts is the old silver dollar.

When some kind customer presents it to view—

The liberty head without necktie or collar.

And all the strange things that to us seem so new;

The wide-spreading eagle, the arrows below it,

The stars and the word with queer things to tell.

The coin of our fathers! We’re glad we know it,

For some time or other ’twill come in right well—

The spreading dollar, the old silver dollar,

The big welcome dollar we love so well.

Although extolling the dollar, Murphy offered his customers bar tokens toward future drinks coins worth 12 and 1/2 cents. As shown below, the Ruby Saloon tokens came in several formats. He also provided advertising shot glasses to his clientele.

Although extolling the dollar, Murphy offered his customers bar tokens toward future drinks coins worth 12 and 1/2 cents. As shown below, the Ruby Saloon tokens came in several formats. He also provided advertising shot glasses to his clientele.

As a result of his success as a saloonkeeper, Murphy could advertise in 1914 that he had been in business for more than 25 years. By that time the Irishman had amassed a wealth of experiences from the history of “The Ruby.” Here are two of them:

Santa Anna’s Knee Buckle

Murphy would be able to recount the day that Texan William Broyles brought to The Ruby Saloon the oval knee buckle of Santa Anna, the former president and military leader of Mexico during the Mexican War with the United States. Santa Anna, shown here, was fond of the ornamentation that went along with the uniform of a high ranking Mexican officer. After the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836, the Santa Anna escaped but was captured the next day. During the next three weeks the general was held prisoner by the Americans until he signed the peace treaty that led to Texas independence.

Murphy would be able to recount the day that Texan William Broyles brought to The Ruby Saloon the oval knee buckle of Santa Anna, the former president and military leader of Mexico during the Mexican War with the United States. Santa Anna, shown here, was fond of the ornamentation that went along with the uniform of a high ranking Mexican officer. After the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836, the Santa Anna escaped but was captured the next day. During the next three weeks the general was held prisoner by the Americans until he signed the peace treaty that led to Texas independence.

During his captivity, it appears that Santa Anna’s uniform was stripped from him, including his oval jeweled knee buckles. Shown here, this was an ornament composed of a metal base and originally set with 22 square jewels, described only as “brilliants.” These might have been diamonds but more likely other clear stones that were cut to emphasize their light-flashing facets. Set at intervals along the bottom edge of the oval pin were four additional rounded gems.

Look closely at the ornament, shown here, and note that four of the jewels are missing. That is where Murphy’s saloon gets involved. The story goes that this trophy from a defeated enemy was given to the victorious General Sam Houston. It subsequently was held by the Houston family until Sam’s daughter, Elizabeth Houston Morrow, for reasons unknown gave it to William Broyles. A patron of Murphy’s saloon, Broyles showed up there one night, possibly a bit of “the drop taken,” pried out four of the “brilliants” and gave them to friends along the bar. Today the knee buckle, still lacking the four jewels, resides under glass at the Museum of History in San Jacinto.

A Shootout over Telephone Service

Perhaps the most bizarre of all the shootouts—and killings—in Texas history originated at the Ruby Saloon. Incredibly, the gunplay erupted over a complaint about Palestine’s telephone service.

R. J. Hiatt was a traveling salesman for the Dallas-based Jesse French Piano Company. His territory included Palestine and Hiatt spent much of his time in that city. Encountering a co-owner of the local telephone company, A. P. Henderson, outside the Ruby Saloon, Hiatt accosted him, shouting that Palestine’s telephone service was rotten. He could not converse over the phone, the salesman said, without being cut off.

Henderson was well aware of the problem. He pointed out to Hiatt that he was being disconnected because of the profanity he frequently used on the telephone. His language was deemed not fit for young female operators to hear. Women at the central office objected to Hiatt’s foul mouth, Henderson said, and were “plugging him out.” The salesman objected to the allegation and called Henderson “a damn liar.” Henderson swung on Hiatt, breaking his nose which bled profusely. Bystanders intervened, ending the fight—for the moment.

Henderson was well aware of the problem. He pointed out to Hiatt that he was being disconnected because of the profanity he frequently used on the telephone. His language was deemed not fit for young female operators to hear. Women at the central office objected to Hiatt’s foul mouth, Henderson said, and were “plugging him out.” The salesman objected to the allegation and called Henderson “a damn liar.” Henderson swung on Hiatt, breaking his nose which bled profusely. Bystanders intervened, ending the fight—for the moment.

As reported in the Palestine Daily Herald on September 16, 1905, Hiatt “had a doctor to dress the nose, and those who observed him afterward, said he brooded over the matter all the afternoon, not saying much or making threats, but his attitude was such that friends, it is reported, warned Henderson to look out, that they thought Hiatt had armed himself. Henderson is reported to have replied in a light vein that he was not afraid; that he could take a pistol away from him, if he should attempt to use it.”

The telephone company co-owner was unwary and it cost him. That evening about seven Henderson was in The Ruby with friends when Hiatt walked in the front door. Shouting “that son of a bitch broke my nose,” the piano salesman began firing. One of three bullets found Henderson’s thigh and he slumped to the floor, badly wounded. Others grappled with Hiatt and took the gun from him before he could fire again.

Hiatt then attempted to escape by running into the Lindell Hotel next door where he had a room on an upper floor. He began to climb the stairs. The newspaper reported: “He was soon followed by City Policeman Jeff Watts. A few seconds later a pistol shot rang out, and parties rushing upstairs found the officer and Hiatt together in the hall, and Hiatt was shot through the body. The man lingered in great agony for thirty or forty minutes, and died….From appearances… he was shot through the back, just to the right of the spinal column, and the ball passed entirely through the body, coming out just to the right of the navel.

Policeman Watts later said he was unaware that Hiatt no longer had a gun when he fired at the fleeing salesman. Nevertheless, Watts, the brother of Palestine’s sheriff, immediately was arrested and incarcerated in the county jail, awaiting an investigation. Meanwhile in a local hospital Henderson’s condition while serious was said by doctors not to be life-threatening.

As for the disposition of Policeman Watts, my guess is the statement he made following the killing proved sufficient to exonerate him: “…He arrived on the scene just after the shooting of Henderson, and hearing that Hiatt had gone in the hotel, followed him, and being told that Henderson had been killed supposed the man was still armed, as he swore to kill an officer if he followed him. They ran onto the third floor, where the shooting took place. Watts says he shot…in self-protection, as Hiatt kept threatening to kill him if he came on. He did not know until afterwards that Hiatt had been disarmed.…” My assumption is that Watts’ testimony, combined with his ties to the sheriff, were sufficient to exonerate him.

The Rest of the Story

With the coming of statewide prohibition to Texas in 1919, Murphy was forced to close down his drinking establishment and while still only 51, census records indicate, turned to operating a drug and tobacco store. Married at 30 in 1893 to Ella Orena Wheeler, a local Palestine woman, Murphy would sire three sons and a daughter. After 1905 he housed his family in a spacious home at 1403 North Queen Street in Palestine, shown here.

With the coming of statewide prohibition to Texas in 1919, Murphy was forced to close down his drinking establishment and while still only 51, census records indicate, turned to operating a drug and tobacco store. Married at 30 in 1893 to Ella Orena Wheeler, a local Palestine woman, Murphy would sire three sons and a daughter. After 1905 he housed his family in a spacious home at 1403 North Queen Street in Palestine, shown here.

Joe Murphy lived to be 80 years old, an advanced age for that time. He must have mused frequently about his decades spent running “one of the oldest and best conducted liquor establishments in Texas.” But even the Texas saloon owner would have to admit that at times events at the Ruby Saloon could get out of hand. Murphy died in October 1943 and was buried in Saint Joseph’s Cemetery, Palestine, He was joined in the grave by wife Ella five years later. Their joint monument is shown here.

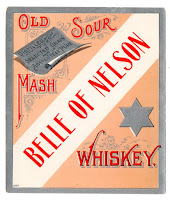

Note: I was drawn to the story of J.J. Murphy and The Ruby Saloon by the trade card that opens this vignette. It led me to the stories of Santa Anna’s buckle and the shootout over disconnected telephone calls. For the latter incident the story as reported by the Palestine Daily Herald, referenced above, was a crucial source.

%20C_pg875_BROADWAY_A-%20CND_29TH_STREET,_SHOWING_IMPERIAL_MUSIC_HALL_AND_DALY'S_THEATRE.jpg)