Martin J. Bligh came to America from Ireland at age 14, settled in Logansport, Indiana, and carved out a 38 year career there selling liquor. His marriages, however, not whiskey sales, would earn Bligh newspaper headlines and intense local interest in his adopted country.

Bligh is an English name generally associated with the Cornwell region. In the early 1700s John Bligh became the Earl of Darnley, creating the first family peerage in Ireland and triggering Bligh family migration to the Emerald Isle. Martin Bligh was the son of Michael and Mary Samidy Bligh. Born in 1861 in Castle Rea, the third largest town in County Roscommon, the boy emigrated to America about 1875 at age 14, most likely accompanied by relatives.

Bligh is an English name generally associated with the Cornwell region. In the early 1700s John Bligh became the Earl of Darnley, creating the first family peerage in Ireland and triggering Bligh family migration to the Emerald Isle. Martin Bligh was the son of Michael and Mary Samidy Bligh. Born in 1861 in Castle Rea, the third largest town in County Roscommon, the boy emigrated to America about 1875 at age 14, most likely accompanied by relatives.

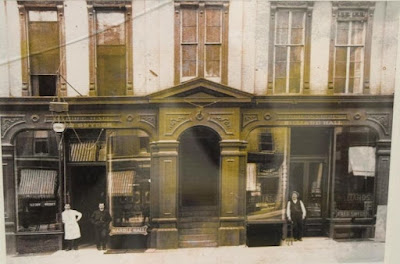

The next few years are shrouded in the mists of history but indications are that Martin was able to achieve additional education. At some point Bligh located in Logansport, Indiana, shown here, that became his home place for much of the rest of his life. Along the way he apparently achieved sufficient experience to open a wholesale liquor house, a venture that proved to be very profitable over a period of the next 35 years.

The next few years are shrouded in the mists of history but indications are that Martin was able to achieve additional education. At some point Bligh located in Logansport, Indiana, shown here, that became his home place for much of the rest of his life. Along the way he apparently achieved sufficient experience to open a wholesale liquor house, a venture that proved to be very profitable over a period of the next 35 years.

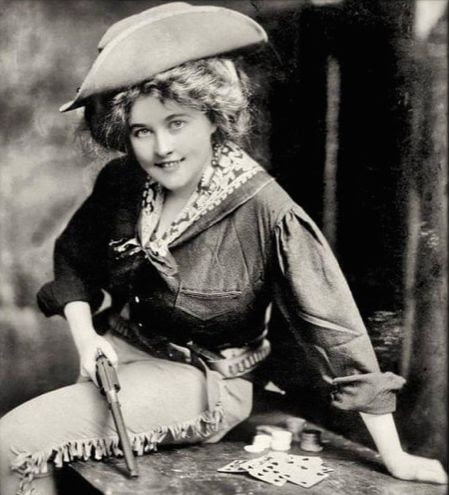

Bligh used a variety of brand names for his whiskey. They included “Dan Dalton,” “Decatur,” “Lone Valley Pennsylvania Pure Rye,” “Old Logan Club,” “Queen of Bourbon,” “Spring Creek,” “Valley Mills,” and “Woodlawn.” Bligh’s flagship brand was “Old Logan Club” shown here in a back-of-the- bar bottle that would have sat invitingly behind the barkeeper.

Another Bligh-gifted fancy carafe to saloons advertised “Queen of Bourbon.” He also gave away shot glasses to favored wholesale and retaiil customers, as shown below. When Congress stiffened trademark laws in 1905, Blight copyrighted that name and all but one other brand (“Valley Mills”). He did so despite the costs that discouraged other dealers from claiming protection for their liquor names. It was an unusual — and expensive — move involving lawyers and other costs but Bligh apparently saw the value.

Along with his busy occupation as a liquor dealer, Bligh was having a complicated — one might say, tumultuous — marital situation. In November 1800, at 19 years old Bligh returned to Europe to be married. His bride was Elizabeth Ann Kelly, daughter of Anne Bergin and James Kelly. Of similar ages, it is possible the couple had been childhood sweethearts. Wed in Yorkshire, England, the new bride accompanied her young groom back to Logansport.

Bligh babies were not long in coming. Their first child was a girl, Anna Hannah, born in 1882, when the couple were each about 21 Anna was followed in 1883 by Michael Francis. Then after a hiatus of four years, Mary Catherine was born in 1887 and Bertha Agnes in 1889. The next two births, sons Martin (1890) and “E.T.” (1893), both died in infancy. Over the years the relationship between Martin and Elizabeth Bligh changed dramatically.

Despite their four minor children, the couple became seriously estranged and Bligh began a new relationship, By now 32 years old and accounted a wealthy man, Bligh divorced Elizabeth and shortly after married 19 year old Katherine “Katie” Eiserlo. The story engendered newspaper stories around Indiana. The Logansport newspaper headlined: “Married Yesterday at Cincinnati by a Justice of the Peace – The Groom Divorced Three Months ago.”

The paper told this story: “The mother of the bride, it is said, objected to the union and she was greatly surprised yesterday morning, upon receipt of a letter from her daughter, worded as follows: ‘Mother – We have gone to Cincinnati. DO not be alarmed. Will return in a few days. – Katie.’ …The marriage occurred at the Palace Hotel…While the affair bears the favor of an elopement, the bride’s father is said to have given his consent to the union, and had been informed of the time and place of the wedding.

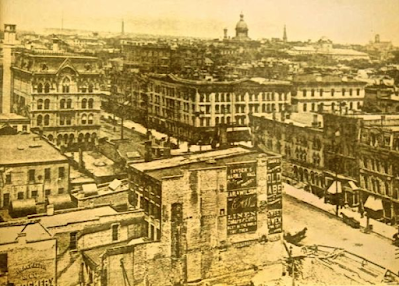

Elizabeth Kelly Bligh, the cast-off wife, was not so easily dismissed. In a suit filed in Kokomo, Indiana, she claimed that in addition to the divorce and payment of alimony she was owed an additional $10,000 in damages for defamation of her character. After pleading that she had no money for a lawyer, Judge Kirkpatrick appointed two retired judges to represent her at the courthouse in Kokomo, shown here, a change of venue required by the intense scrutiny of the case in Logansport.

Elizabeth Kelly Bligh, the cast-off wife, was not so easily dismissed. In a suit filed in Kokomo, Indiana, she claimed that in addition to the divorce and payment of alimony she was owed an additional $10,000 in damages for defamation of her character. After pleading that she had no money for a lawyer, Judge Kirkpatrick appointed two retired judges to represent her at the courthouse in Kokomo, shown here, a change of venue required by the intense scrutiny of the case in Logansport.

In her complaint for damages, Elizabeth charged that Martin had written a letter to her brother in which her he accused her of immorality and drunkeness, while she temporarily had returned to Ireland after being abandoned by her husband. Bligh promptly countersued. As reported in the Indianapolis Journal the ex-husband in an affidavit claimed that: Mrs. Bligh was possessed of $10,000 worth of real estate, and has diamonds, horses and carriages and other personal property of the value of $10,000 more, and asked that the appointment of attorneys be set aside… The trial on the main issue commences Monday, and will be a prolonged contest. Although I have been unable to find the outcome of the trial it is problematic that Bligh, known to be a wealthy man, could have walked away without some monetary judgment against him. Elizabeth, with at least some of the children, promptly moved to Toledo, Ohio, where she apparently had relatives.

In the meantime Martin and bride Catherine set about creating a new family. Their first child, Thomas H. was born in 1895, followed by Edgar J. in 1898. Two daughters followed, Bonita A. in 1900 and Almytra in 1904. The couple’s last child, George, was born in 1909. All lived to maturity. To house his family Bligh provided a large house at 1209 High Street in Logansport, shown here.

In the meantime Martin and bride Catherine set about creating a new family. Their first child, Thomas H. was born in 1895, followed by Edgar J. in 1898. Two daughters followed, Bonita A. in 1900 and Almytra in 1904. The couple’s last child, George, was born in 1909. All lived to maturity. To house his family Bligh provided a large house at 1209 High Street in Logansport, shown here.

Bligh appears to have redeemed his reputation in Logansport despite the contentious divorce and scandalous remarriage. He continued to operate his liquor house in Logansport until 1918 when Indiana passed a law banning the sale of alcoholic beverages. It had proved to be a lucrative business, complementing a lumber and coal yard Bligh also owned. The local press accounted him a “power’ in the Republican party in Cass County, Indiana, calling Bligh a: “A keen businessman, very resourceful, a staunch friend….”

Bligh subsequently moved 24 miles to Rochester, Indiana, where he had farming interests. Over the next few years he suffered financial reverses leading to his retreat in 1925 from Rochester back to Logansport. The local paper there speculated: “When reverses overtook him he did not show it in his demeanor and his friends believed that if his health had not been bad he would have over come his financial difficulties before he died.”

Bligh’s death certificate testified to the story. He was stricken with heart problems beginning in March 1927 and under the care of doctors for the next two years until he died of a brain clot on April 5, 1929. Katherine and his children, all now adults, were gathered for his funeral at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. He was buried in St. Vincent Cemetery. Bligh’s grave stone is shown above, along with Katherine’s who passed away 32 years after her husband. In a final irony, Elizabeth, Bligh’s cast-off wife, also is buried in St. Vincent’s.

Note: The sources for much of this post on Martin Bligh are stories from Indiana newspapers.