Whiskey Men & “Murder Most Foul”

Foreword: In Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” the ghost of the poisoned king of Denmark tells his son of his killing, terming it, “Murder most foul.” Whiskey men have been involved in homicides that might be similarly described, as bystander, victim or perpetrator, as related in the brief stories to follow. The three incidents are linked by the reality that justice was not done in any of them.

Whatever sense of satisfaction Paterno felt as a leader of a significant portion of the Italian community in New Orleans, the year 1890 would change everything. New Orleans was undergoing a period lawlessness, corruption and unrest. On the night of October 15, as the New Orleans police chief, David Hennessy, was walking home he was gunned down on the street. As he lay dying he is reputed to have whispered, “The dagoes did it.” A mass arrest of Italian-Americans and Italian migrant workers followed. Many were Paterno’s friends and adherents.

From his position of leadership, Patorno vigorously argued against the arrests. At the same time he deplored the Hennessy murder. He told a Daily Picayune reporter that as a New Orleans citizen and merchant he would do all in his power to “support and protect the honor and welfare of the city.” Among those taken was his brother, Charles, who is said to have had a strong resemblance to Antonio.

The lynchings caused an international incident. The Italian ambassador demanded that the U.S. government take action to protect Italians and provide restitution. There were rumors of war between Italy and the U.S. The threat passed when President Benjamin Harrison ordered a U.S. government award of $25,000 (equivalent to over $600,000 today) to the families of Italian citizens who had been lynched. The perpetrators of the lynchings went free.

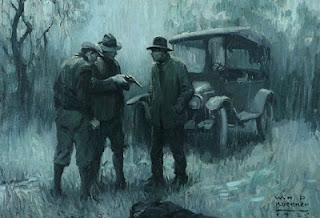

Through intermediaries, likely fellow Italians, he made contact with a New York City gang headed by Meyer Lansky who ran a prominent bootlegging operation. Salamandra presumably made a deal to sell 51 cases of whiskey to the gangsters, worth in today’s dollar more than $600,000. The conspirators agreed to the liquor handoff near Kingston, New Jersey, about 14 miles north of Trenton. There the money was to be turned over.

On the night of February 13, 1921, with Salamandra and a brother following in their automobile, a truck carrying the whiskey set out from Trenton for the rendezvous. The liquor dealer apparently was apprehensive about the deal as he and associates were armed with pistols. As they neared Kingston about three a.m. suddenly a Cadillac touring car with four men in it — hired by Lansky — pulled up beside them, pistols drawn, and forced both the truck and Salamandra’s car off the road. A gun battle ensued. Leo Salamandra was shot five times at close range and died on the spot.

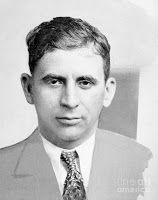

Tired, Motlow headed for a Pullman berth. A black sleeping car porter named Ed Wallis asked Motlow for his ticket. When Motlow was unable to produce one, Wallis refused him a berth. Motlow became enraged at being balked by a person of color. Hearing their argument, Conductor Clarence Pullis, who was white, tried to intervene. As the train slowly made its way through a downtown tunnel toward the Mississippi, Lem reached for his pistol, apparently to shoot Wallis. In his drunken state, he fired two shots, one errantly, the second striking Pullis in the abdomen.

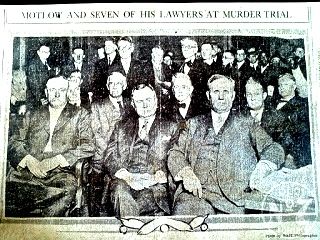

Taken off the train, Pullis died in a local hospital, leaving his widow and two minor children. Motlow was charged with murder. St. Louis newspapers gave the story front page treatment. Local sentiment ran high against the Tennessee distiller. As a wealthy man Lem had ample resources at his disposal. He hired a phalanx of top lawyers as his defense team. They built their case on Wallis being black.

No subtlety attended the defense making race the issue. In closing arguments one of Motlow’s lawyers declared: “There are two kinds of (blacks) in the South. There are those who know their place … and those who have ambitions for racial equality. … In such a class falls Wallis, the race reformer, the man who would be socially equal to you all, gentlemen of the jury.” The all white, all male jury took little time in bringing a verdict of “not guilty.” The foreman told reporters: “We didn’t believe the Negro.” Jurors shook hands with Motlow as he left the courtroom on December 10, 1924 — a free man.

In each of these three cases “murder most foul” went unpunished. All the killers went free. Only one perpetrator was tried and by virtue of a racist defense, acquitted. Not only was justice “blind” in each incident, it was entirely absent.

Note: Longer vignettes on each of these whiskey men may be found on this site:Antonio Paterno, September 2, 2018; Leo Salamandra, November 10, 2019; and Lem Motlow, November 26, 2019.